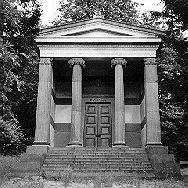

East Finchley's CemeteriesTwo fascinating exhibitions of sculpture and social history are on show daily in East Finchley, London, for the foreseeable future. They are East Finchley cemetery (until recently called St Marylebone Cemetery), in East End Road, and St Pancras & Islington Cemetery, in the High Road. By the mid nineteenth century the churchyards and private burial grounds of central London had long been a scandal, being so full that bones could often be seen poking through the ground. Private cemeteries, such as Kensal Green, had been built away from the centre, but were too expensive for most people. In 1852, however, the Metropolitan Burial Act allowed public money to be spent on providing cemeteries, and St Pancras Cemetery was the first result of this. Designed by the firm of Barnett & Birch, it opened in 1854 on 88 acres of Horse Shoe Farm on Finchley Common. In 1877 it added another 94 acres and became the St Pancras & Islington Cemetery – the largest cemetery in London. Its finest feature is usually reckoned to be the mausoleum in the form of an Ionic temple erected for the millionaire German industrial chemist Ludwig Mond (1839–1909). His collection of early Italian paintings is now in the National Gallery. |

|

| The Mond mausoleum |

| But there are also quirkier pleasures to be had. The splendid statue of the road-sweeper

and original pearly king Henry Croft (d. 1930) was too often wrecked by vandals and has now been replaced by something

simpler, and the stone balloon of the aeronaut Percival Spencer (1864–1913) is awaiting replacement; but a kilted Scotsman, Alexander Lamond ('My Alick',

d. 1926), remains (though it does not answer the perennial Celtic sartorial question),

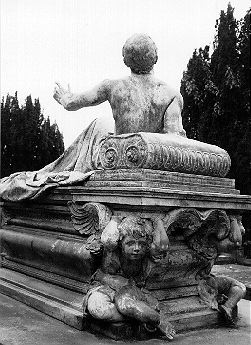

as does the parachuting figure on the memorial to the 'famous Lyceum clown' Harry Gardner (1800–51) – though the parachute is not his. Now submerged by undergrowth is the Pre-Raphaelite

painter Ford Madox Brown (1821–93). The St Marylebone Cemetery – also designed by Barnett & Birch – was founded in 1854, and the prosperity of St Marylebone in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century resulted in some splendid monuments, including a dying (or resurrected?) youth on the tomb of Thomas Tate, a draped mourner over Harry Dillon-Ripley, an angel hovering over a muscular blacksmith beneath a bust of the engineer Sir Peter Nicol Russell, and a Napoleonic tomb for Thomas Skarratt Hall. |

|

| The tomb of Thomas Skarratt Hall (d. 1903) The base used to have a bronze angel at each corner, but these were stolen in 1989 |

|

| |

| The tomb of Thomas Tate (1832–1909) | The monument to Harry Dillon-Ripley (1864–1915), by William Reid-Dick |

The great dancer Vaslav Nijinsky (1888–1950) was buried here until his body was removed to Montmartre in 1953. Among those who remain are the conductor Leopold Stokowski (1882–1977), one of whose claims to fame is that it is his hand that Mickey Mouse shakes at the start of Fantasia; Sir Edmund Gosse (1849–1928), the critic and author of a fascinating autobiography, Father and Son; Quintin Hogg (1845–1903), the founder of Regent Street Polytechnic; Thomas Huxley (1825–95), the early champion of Darwinism; the great music-hall clown Little Tich; and Jimmy Nervo (1897–1975) of the Crazy Gang. Lord Northcliffe, founder of the Daily Mail, is buried near his parents, and his brother and fellow newspaper magnate Lord Rothermere also lies nearby. An unmarked grave contains the remains of David 'Baba' Williams, a Trinidadian saxophonist who was among the many, including fellow members of Ken 'Snakehips' Johnson's band, who died when a bomb hit the Café de Paris on 8 March 1941, at the height of the Blitz on London |

The monument to Sir Peter Nicol Russell (1816–1905) |

|

| |

| 'My Alick': the monument to Alexander Lamond in St Pancras & Islington Cemetery | The erotics of mourning: the monument of Leonard John Hawkins (1890–1934) in East Finchley Cemetery. The monument is presumably a stock design: there is a smaller version in Hampstead Cemetery. |

But in both cemeteries the stones of those who were never well known are often no less interesting (and the inscriptions are far more personal than you are allowed in C of E churchyards nowadays). Clasped hands – a symbol of farewell – are common in both, and the honours are about even for angels (though the Catholic section of St Pancras & Islington has a particularly splendid group on the grave of Frank Manzi (1913–1962)). But why is it that Celtic crosses are so well represented in St Marylebone and broken lilies in St Pancras? For some people, of course, cemeteries contain not just social history but personal history, and may not be the cheeriest of places. For me, though, they are celebrations of human affection and individuality, and the only depressing feature is the handiwork of vandals who presumably cannot imagine feeling affection for anyone or anything.

Chris Brooks, Mortal Remains: The History and Present State of the Victorian and Edwardian Cemeteries (Exeter: Wheaton, in association with the Victorian Society, 1989) James Stevens Curl, The Victorian Celebration of Death (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000) Hugh Meller, London Cemeteries: An Illustrated Guide and Gazeteer (London: Scolar Press, 2nd edn, 1985) |