AN ENGLISH CUBIST

WILLIAM ROBERTS:

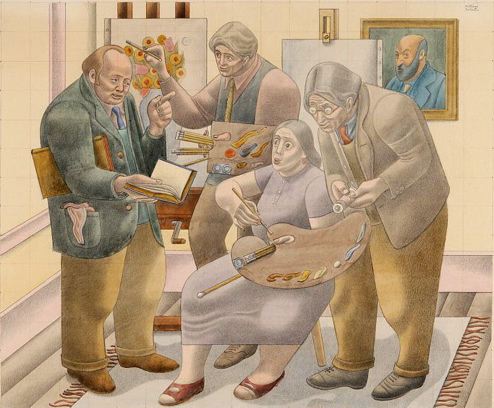

Art Critics and Dealers

This piece first appeared in William Roberts, Five Posthumous Essays and Other Writings (Valencia, 1990). © The Estate of John David Roberts.

No! No! Roger, Cézanne Did Not Use It (drawing and watercolour), 1934

© The Estate of John David Roberts

Although from about the year 1911 Lewis had shown a large number of paintings publicly in various galleries, it was not until June 1914 with the production of BLAST that he began to call himself a VORTICIST. What was he then before that, from June 1911 till June 1914? Certainly not a Vorticist, for the word had not yet been invented. The only word that could describe the character of his work during that first period was Cubist or Rebel Art. My own Cubist work, too, that appears in the first pink BLAST, had all been done in 1913 and the beginning of 1914. After that, the work done for the second white BLAST and that shown at the Doré Gallery in mid-1915, carries for the first time the Vorticist label, and for a period of no more than twelve months. After the Doré exhibition there is an interval of five years, until in the Spring of 1920 a Non-Vorticist Group exhibition with several new members, and McKnight Kauffer as Secretary, is put on at Heal's Mansard gallery. Moreover to confirm that Vorticism is finished, a new slogan is adopted, GROUP X. However after this first exhibition the group disbanded.

There followed a long 29-year period of silence, and it would seem that the old Vorticism had been long forgotten.

Even in the May 1949 Lewis retrospective exhibition at the Redfern Gallery, he stresses in his introduction the naturalistic side of his painting, and makes only a passing reference to 'The Days of Vorticism' as of something long since finished. But we now come to July 1956 forty-one years after the 1915 show, and forty-one years without a word as to Vorticism. We are at the Tate Gallery, where there is another Lewis retrospective exhibition taking place, and we are told by Sir John Rothenstein in his Introduction to the Catalogue that this is a show of 'Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism.' But there are included also some oddments of the work of what the Catalogue calls 'Other Vorticists'. This whole display makes a fine send-off for Lewis, but is not so good for the 'Other Vorticists'. The Catalogue, chock full of dates and details, will be extremely useful in showing the art critics of the future what its compilers considered Vorticism to be in 1956. All this is confirmed by Lewis's own statement in his introduction: 'Vorticism, in fact, is what I personally did and said at a certain period.'

This 1956 Tate Exhibition was followed by another silence lasting 13 years, until my d'Offay Gallery show of 1969. One would have expected that, with the death of Lewis, Vorticism would have passed away too. But no, after 13 years of quiet it came back stronger than ever, in spite of my attempt to avoid the term Vorticism. From my show of drawings at Anthony d'Offay's Gallery in September 1969 and our conversations regarding Vorticism came his plan for a book on the subject. The result was an attractive volume, well-arranged, which dealt with all the artists producing abstract painting at that period: it was well-illustrated with coloured reproductions and not overloaded with explanatory literature or aesthetic analysis.

It was about this time that an undergraduate from Cambridge named Cork, seeking a subject for his Tripos, became acquainted with the d'Offay Gallery and the book on abstract painting. It is an interesting thought that our decision to leave out the word 'Vorticism' in the d'Offay book gave Cork the opportunity to come forth as the champion of Vorticism. However I do not think that d'Offay at that time realised what Cork's intentions were, or that five years from 1969 a large Arts Council book with the title 'Vorticism and its Allies', packed with illustrations and commentary by Cork, would supersede his own publication 'English Abstract Art.' Cork has claimed that when he began his researches into Vorticism 'the dearth of published information about the subject was as shameful as it was acute.' But if he had cared first of all to carry his researches back to 1956 when Lewis had his show at the Tate, he would have found plenty of publicity upon the subject.

However, at that date Cork would have been about seven years old, hardly the age at which to be interested as to whether Lewis was the only Vorticist or not: for the days of the Tripos were yet far off. During the next five years from 1969 Cork was busy collecting information. In his requests to me for interviews he was not successful.

Rumours were now beginning to circulate that an exhibition of Vorticism was to be organised by the Arts Council, while at the same time a book on this subject entitled 'Vorticism and its Allies' would be published with an introduction by Cork, who had moreover established himself as an art critic by a weekly article in the Evening Standard. This new job would be of great value and enable him to dispense approval or personal gibes as he felt inclined. As I wished to avoid a repetition of the Lewis–Rothenstein–Tate Gallery affair, I took the precaution of preparing a small pamphlet entitled 'In Defence of the English Cubists,' which I distributed a few weeks before the opening of the Arts Council Exhibition. Cork, in angry mood, replied to this in an article in the Evening Standard (2.12.76) which served besides as a useful piece of publicity for the 'Vorticism and its Allies' show. [Roberts has evidently confused the date of this article, actually 28 March 1974, with the date of Cork's review of the exhibition at the Michael Parkin Gallery mentioned below.] With the opening of the Exhibition somewhat later, it seemed that at last the final word had been said, and Cork's exploitation of Vorticism was ended.

However our optimism as to this was much misplaced. Cork had by no means finished; in fact it would be more correct to say he was only just beginning. For in less than two years after his 'Vorticism and its Allies' show the indefatigable Cork produced two more volumes on the subject with the imposing title 'Vorticism and Abstract Art in the First Machine Age,' large cumbersome twin volumes whose weight alone will discourage any attempt to read them; and even if the weight is overcome, there is still the little matter of price, £30 each tome. In order to blow up the subject in this fashion there must be a good deal of irrelevant matter stuffed between these hardboard covers.

Because of the likelihood of this happening I have always declined to co-operate with anyone wishing to write about the events of those few months in which our abstract paintings were done. For everyone who touches the subject will endeavour to leave their mark upon it with new discoveries, fresh revelations, and their significance. For instance, Cork's presentation of Arbuthnot's so-called 'Abstract' photographs, which are merely ordinary examples of realistic photography, entirely out of place in a book on Abstract painting, and not really connected at all with Vorticism. Also the American Coburn's so-called abstract photographs were scarcely part of Vorticism either, as they were done in 1917, when we were, at that date, Lewis in the Garrison Artillery, and myself in the Field Artillery, in Flanders. What, we might also ask, is Augustus John doing in a book on Abstract painting?

Besides establishing himself as an authority on Vorticism with the aid of his 'Vorticism in the First Machine Age,' Cork has secured himself a place in the history of Art, among this small group of abstract painters, and this has been the main object of his researches from the start. Besides being an Art critic, Cork is also a newspaper man with a weekly criticism in the Evening Standard, together with his photograph. This show a cadaverous-featured individual, long-haired and wearing an extra-large-sized pair of spectacles; the ensemble expressing self-assurance and [word omitted].

Richard Cork in 1972

(Photo by Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

It was on one of his journeys in search of a subject for his weekly column that Cork dropped in at a small Gallery situated in the 'Far West' of Kensington. This gallery consists of a small ground-floor room and a basement, and displays the name of its owner Parkin. As luck would have it, there was, unknown to me, a collection of my work on show, and this gave the Dealer and the Critic an opportunity to twist Roberts' 'Private Image' into his 'Public Caricature.' Parkin is one of the New Deal type picture dealers, the kind who writes his own introductions and criticisms upon the character and work of the artists he exhibits, nor does he mind overmuch should it turn out to be unfavourable to them.

So in his introduction to the catalogue of this show, Parkin, quoting John Rothenstein and the 'Observer' newspaper, describes me as a 'recluse,' an 'eccentric,' and a 'loner.' Cork, following on his visit to dealer Parkin's Salon, in his weekly Evening Standard article adds some important touches of his own to my 'Public Caricature.' He finds Roberts to be 'a notorious recluse,' 'a hermit,' 'accused of outright misanthropy,' is 'waspish and angry,' has also 'enduring bitterness.' It is obvious that this type of Art Criticism has its proper place among the Evening Standard accounts of Rapes, Dope Peddling, Muggings, Kidnappings, and the like.

What then is the reason for the resentment of the dealer and the critic? For Cork, it is my refusal to assist him in his exploitation of Vorticism. For Parkin, my refusal to take part in his exhibition. Although the pictures on show were done by me, they are now however the property of other people, and they did not come directly from me. Parkin ends his introduction with the pious hope 'that in some small way this exhibition will help Roberts.' But how this could be I fail to see, for he knows full well that the only persons it is likely to help at all are the owners, and the Art Dealer Parkin.

Besides their eagerness, already noticed, to present a 'public caricature' of me in their gallery catalogue and newspaper, this couple have much else in common – for instance an immense admiration for Louis Wain's drawings of cats and kittens. Parkin for his part finds it useful to put these cat pictures on show from time to time when there is nothing else available. With regard to Cork he should be of good cheer, Parkin may yet find a Vorticist cat or two among his collection. I recall Lewis remarking to me in disgust, one day as we stood on the entrance steps of 18 Fitzroy Street where he then lived, 'All the cats of the neighbourhood come and shit on my doorstep.' But these couldn't have been Art-loving Vorticist cats, although the patterns they left on the flagstones had a certain abstract character.

In an extract taken from his final three-column article of farewell in the Evening Standard of June 2nd 1977, Cork has this to say about the role of the art critic; 'The critic can help to bring a new awareness into being, by sometimes prompting artists to see themselves as part of a larger purpose, which can only be properly clarified through verbal analysis and argument.' However in an earlier article in this same newspaper, Cork shows how the critic through verbal abuse can also prompt artists to see themselves as: 'Loners, recluses, hermits, angry, waspish, notorious, outright misanthropists.'

This recluse accusation was first made in 1971 after a visit my wife and I received from an Observer newspaper reporter named Barrie Sturt-Penrose. We entertained him with coffee and homemade cake; in return, he went back to his paper and named me recluse. It was repeated and enlarged upon in a catalogue introduction by art dealer Parkin in 1976, then further developed later in an article in the Evening Standard by Cork. I have never met Parkin or Cork. They have formed my public caricature with the printed inventions of Barrie Sturt-Penrose and additional falsehoods of their own. Very little is published concerning the characters and tastes of present day art dealers and critics, their 'Public Images' are practically non-existent. It would be helpful to know how they came to be art dealers or art critics, whether they are 'Playboys' of the art world, or just solitary figures, 'Loners,' as it were. Some art dealers are engaged in other businesses as well: accountants, solicitors, actors, traders in antiques, even retired tailors. Surely, there is a need here for a 'Friends of the Artists' Protection Association?

News | Gallery | Auction results | The artist’s house | Contact

List of works illustrated on the site

Catalogue raisonné:

chronological | alphabetical