AN ENGLISH CUBIST

WILLIAM ROBERTS:

Dealers and Galleries

This piece first appeared in William Roberts, Five Posthumous Essays and Other Writings (Valencia, 1990). © The Estate of John David Roberts.

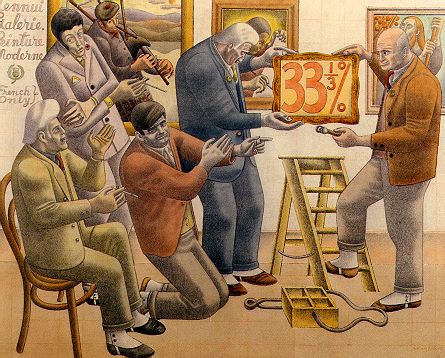

Hanging a Masterpiece (pencil and watercolour), 1934

© The Estate of John David Roberts

MARCHANT OF THE GOUPIL GALLERY

The Goupil Gallery ceased to exist sometime in the early Thirties. It formerly occupied the ground floor of a building in old Lower Regent Street, before it was rebuilt, where an Angus Steak House now stands. The Gallery interior was lined throughout with a dark crimson fabric that made a good background to the Steers, Whistlers, Sickerts and Johns hanging on the walls. The entrance and corridor to the inner rooms were guarded by a bespectacled grey-bearded old man in a long faded green overcoat; the finishing touch to this attire was a hat with a shiny peak, his symbol of office, it would seem. Marchant was the name of the Gallery owner, his Christian name [William] I cannot recall; however, Marchant seemed to be all that was needed. There was something 'd'un monsieur Français' about his appearance, with his ample white hair brushed back, and moustache of similar colour waxed at the ends. He needed only the red ribbon of the Legion d'Honneur to complete the illusion. From time to time he would give a little sigh of contentment as if he had just finished a delicious meal. He once remarked to Bernard Meninsky: 'If you only knew how many lunches I have to give a client, to sell him one of your drawings!' However I fancy this necessary wining and lunching greatly helped to ease the labour and strain of Marchant's salesmanship.

The first private view of the newly-formed London Group was held in the Goupil Gallery. There was a large noisy gathering of members and their friends on that Autumn afternoon of 1914. Also on that occasion there was a lively encounter between David Bomberg and Wyndham Lewis. Bomberg accused Lewis of removing from the wall one of his paintings, and putting up one of his own in its place.

Soon after the ending of the first World War, Lewis had a show of drawings at the Goupil. 'Never again', was Marchant's comment to me when the show ended; he did not say why he had come to that decision. On the other hand, he was much happier with the financial results from an exhibition of a batch of 'Mother and Child' drawings that he had bought cheaply from Meninsky; a deal that this artist continued to lament ever afterwards. My first business relationship with Marchant came when one day I slipped past the old doorkeeper and introduced myself to the Gallery secretary, Mr. Yockney. Following this escapade, Marchant made a 'gentleman's agreement' with me; this was to paint for him three landscapes at £21 each. I was to be paid by instalments, and had to bring my painting to the Gallery from time to time for his inspection. Although I was not aware of it, there was in the background a sort of guarantor to this proposition; a patron of my student days, Sir Cyril Butler.

At the far end of the Goupil's main gallery, a stair led to an upper room also decorated in dark-toned crimson. It was here that selected paintings were shown to important clients. There was a small round window in this room that enabled Marchant to see and hear what went on in the Gallery below, without being seen himself. He once referred to the Goupil, meaningly, as a 'regular Whispering Gallery', and he was anxious not to miss a 'Whisper'.

Arriving at the Gallery one morning to collect my weekly instalment, on the opening day of an exhibition of the work of Walter Greaves, I found myself among a crowd of reporters and photographers. The centre of interest was Greaves, a small slender figure hidden under a large black sombrero. Sickert had nicknamed him 'Tiny' Greaves. Some of 'Tiny's' fame almost splashed over on me, when in error the photographers wanted to put me in the picture alongside Greaves; but Marchant hurriedly pulled me aside, exclaiming 'No, not him.' On one occasion I overheard Marchant on the 'phone, giving advice to someone in this fashion: 'Well, let him have the money, but not at once, make him wait a bit; don't let him think he is getting the money just because he asked for it. Make him wait.' I guess this must have concerned a transaction between patron and artist; rather in the same vein as Keynes's remark: 'If you give an artist money, he won't work.'

I had finished the second of the three paintings for Marchant, but had not begun the third, although I had received a small sum on account, when Knewstub of the Chenil Gallery offered me a one-man show, which I accepted. On learning of this arrangement, Marchant was furious, and claimed that I still owed him another picture. He rejected my suggestion that he should wait and choose something from my coming Chenil exhibition, and insisted that I must bring my third painting first of all to the Goupil instead. However before this took place Marchant died. Thus it was to his wife, who continued to carry on the business for a while, that I delivered a painting that was never completely paid for.

KNEWSTUB OF THE CHENIL GALLERIES

The original Chenil Gallery was an old Georgian house situated between Chelsea Town Hall and the Six Bells Public-House. It was here that Knewstub carried on the combined businesses of Art dealer, artist's colour-man, and picture-frame maker. The art dealing part was run chiefly for the benefit of Augustus John, whose work was permanently on view in the Gallery. John also had a large studio in the garden behind the main building; it was here that John's large war cartoon for the Canadians was done. Knewstub was a very cheerful person, always ready for a little fun; his round smiling face topped by a shock of fair curly hair had earned him the nickname of the 'Cherub'; Millais' 'Bubbles' grown up, as it were. He wrote to me whilst I was still a student at the Slade, but I'm afraid I was not ready at that time for such a plunge.

Sometime, just before the 1914 war I think, Bomberg had an exhibition at the Chenil; the 'pièce de résistance' of the show was a large painting called 'The Mud Bath.' It was much too big to get into the Gallery, so they hung it up over the entrance outside in the street. A sample, this, of Knewstubbian humour. But there was another side to his character besides waggishness. In those days the favourite meeting place for artists was the Café Royal; and their favourite eating place, for art dealers too of course, was the old Sceptre, a chop-house facing the rear entrance of the Café Royal. The Sceptre was renowned for its steal and kidney pie and was always crowded with appreciative customers. At one of these animated mealtimes I recall seeing Knewstub dining with Gerald Brockhurst, the painter of highly finished portraits. Knewstub told me once how he had helped Brockhurst, who was practically penniless and had been compelled to sell the gold medal he had won in a drawing competition, when a student at the Royal Academy schools. However at this moment of dining they seemed two gay cronies quite free from care.

Also on this same evening as if to balance the gaiety at Knewstub's table, a squabble occurred between Bomberg and Gaudier-Brezska. The Sceptre had the old-fashioned high-backed seats characteristic of the earlier type of eating-house. It so happened that at the other side of the high-back against which Bomberg and I were sitting, Gaudier could be heard explaining his views on Cubism. This loud talk irritated Bomberg, and he began to imitate the sculptor's remarks. Suddenly there was a commotion in the other compartment, and Gaudier's face appeared above the back of our seat, at the same time shouting furiously that if Bomberg didn't stop it, he would throw him out. However Bomberg would not have been an easy person to throw out; I know of three separate incidents in which his opponent failed to get the better of him.

After the Sceptre, the evening usually ended with a visit to the Café Royal, by way of the back door. This was how the less affluent habitués preferred to enter the Royal; because it was at the back part that one was allowed by a friendly waiter – Papani for instance – to sit the evening out, with a single absinthe or café-au-lait. Also one had a good view of the whole Café and the main door through which the more distinguished clients made their entrance.

I have watched from a back row table the arrival of quite a number of celebrities. The night Aleister Crowley arrived from Paris, waving triumphantly the gold fig-leaf snatched from Epstein's statue on the tomb of Oscar Wilde in the Père Lachaise. The entrance of the popular music-hall singer Lilian Shelley, flamboyant in leopard-skin coat and surrounded by an escort of admirers. And the stir caused in the Café when Nijinsky, wearing evening dress and top hat, entered accompanied by Diaghileff and other members of the Russian Ballet.

Another event that made an evening to remember was the arrival in the Café of a group of Rumanian Gitanos, with their guide, a little man sporting a large sombrero, the secretary of the Gypsy Club with premises in Lower Regent Street. Augustus John, seated with his friend Ian Strang, became annoyed when the guide led this picturesque collection of Gitanos to another part of the Café. Perhaps John, a frequenter of gipsy camps, who spoke the Romany lingo and wore gold ear-rings, felt himself slighted. Whatever the cause, at closing time, when we had all filed out into the street, John approached the little guide and smacked his face.

Some bystanders soon collected, and this brought two policemen to the scene; after listening to the victim's complaint, they asked John why he had done it. 'I don't like him,' Augustus replied. The constables seemed to think this a satisfactory answer, and after telling the onlookers to move on, continued on their beat, whilst John and Strang strolled off in the direction of Oddenino's.

About 1920 Knewstub offered a second time to give me a 'One Man' show. On this occasion, with the financial assistance of Eric Kennington, I managed to get sufficient work together to fill two small rooms of the Chenil Gallery. The show got little notice. A newspaper art critic wrote: 'If anyone deserves to wear the crown of success, it is William Roberts.' Mark Gertler came, took one look and hurried away.

Augustus John's visit was longer; Knewstub told me afterwards that he objected to the two small dogs sniffing each other's rear ends, in my painting 'Bank Holiday in the Park.' John suggested that it should be taken out of the show, but his advice was ignored. There was also on display a small etching of people drinking; its title 'The Boozers', brought a protest from Knewstub himself. It was obvious that both the artist and dealer were critics of rare sensitivity. When the exhibition was nearing its end I asked Knewstub for a small payment in advance. After this long lapse of time I cannot remember whether I got the sub or not; but I shall never forget the remark he made at the time: 'I shall never be subjected to this again.' His attitude puzzled me, as I felt the embarrassment was more mine than his.

Muirhead Bone, who had written an introduction to the catalogue of the show, brought Frank Pick, head of the Underground, to see it. As a result of their visit I was asked to do a poster, to be put up at the entrance of the British Trade Fair at Wembley. It was to be in two sections, about thirty feet over-all in length, and some eight feet in height. The poster was to illustrate the development of the bus, from the horse-drawn to the mechanical.

The painting was done in a large, dingy petrol-smelling shed, part of a bus dépôt in Chelsea. Outside, adjoining my impromptu studio, was a spacious courtyard where bus-drivers practised skids, on ground made slippery with oil and water. Before I began the poster Bone decided the job would be too much for one person, and brought in Neville Lewis to paint one of the sections. Lewis, a South African, was known as 'Nigger' Lewis, because of his frequent use of negresses and negroes as models. I fear Lewis did not get much inspiration from his new model: the motor bus. His visits to this grimy bus dépôt were very irregular, and once in desperation he suggested that I should paint his portion as well. But 'Nigger' made no mention of payment.

Soon after my exhibition, Knewstub began to form ambitious plans for a new and magnificent Chenil Gallery. The old Georgian redbricked house that had been the original Chenil was demolished, and in its place emerged an imposing building in grey stone; at the rear and connected with the main building was a garden with a pool where John's studio had been.

The new Chenil started its career with a large exhibition of the work of Augustus John. The private view brought together a crowd of enthusiastic visitors, and John had difficulty in making his way around the packed Gallery. Following this excellent beginning, the recently formed 'National Society,' a group that was intended to include artists of every creed and 'Ism', took over. A new venture for an Art Gallery in the 1920's was the introduction of orchestral concerts and chamber music.

Besides the periodic exhibitions of pictures in the Gallery, art classes were to be held in the upper part of the building, to which eminent artists were to be invited to come and act as visiting instructors. But I am afraid the proposed art school did not materialise. Despite Knewstub's optimistic manner business was slack, and the bankers began to take more interest in the Gallery than did the artists. I remember a visit I paid to the Chenil one November Saturday afternoon, and found one solitary man studying the paintings. Knewstub in a whisper informed me that the lone visitor was Sir Samuel Hoare, our Minister for Foreign Affairs; then added in a more determined voice: 'I'll get them in here yet.'

But in those early days of the Twenties 'Getting them in' was not as easy as it is today. At that period there was no Arts Council finance to lend a helping hand, no B.B.C. broadcasts to advertise you, nor television interviews to help you 'get them in.' Unfortunately Knewstub, with his Art Gallery-Concert Hall-Art School ensemble, was way ahead of his time.

Knewstub, seeking support, endeavoured to interest Roger Fry in his venture, but Roger advised him to try dealing in Old Masters. A dealer by the name of Turner, with a Gallery in the neighbourhood of Bond Street, who dealt only in modern French paintings, had also been invited to join the Chenil. But his reply had been, referring to his own Gallery – 'Ici je suis, ici je reste.' Finally, retreat was the only course left for Knewstub. A firm in need of a factory in which to produce and distribute 'Pop Group' records, took over the Gallery for a time. But today it stands empty, a melancholy reminder of the unsuccessful attempt, more than fifty years ago, to give to the artists' colony of Chelsea an Art Centre and Gallery of their own.

Several years after the collapse of the Chenil, in a street on the outskirts of Hastings, I saw a man with a horse and cart selling fruit and vegetables from door to door. His face seemed familiar to me, and as I overtook him I recognised Knewstub. He showed no desire for conversation, and my astonishment left me without words. I had never expected to see the one-time Chenil Gallery Director as a street trader of vegetables. His last years were spent in a Sussex village, away from the worries of business schemes and the turmoil of the King's Road.

THE MAYOR GALLERY AND THE LONDON ARTISTS' ASSOCIATION

In the early 'Thirties' besides the Leicester Galleries there were also other dealers who took my work. One of these was a young man who liked to dress well and live in the style of a man-about-town, named Freddie Mayor. His father, a water-colour artist, a former member of the Chelsea Arts Club, had died a short while before, and some of his friends and fellow Club members had raised a fund to set his son up as an Art dealer. It was soon after this event that I encountered Freddie, and for a while showed work in his Gallery. But the business failed and the gallery closed down, so Mayor was out of a job.

But he soon succeeded in obtaining the post of secretary to a recently formed Art Group called the London Artists' Association. It comprised four wealthy gentlemen known as the 'Guarantors' whose aim was to promote the sales of the artist members of the Group, and give them a small allowance to be refunded from the sale of their work. The 'Association' had a special interest in helping its young and struggling members. The names of the Guarantors were: Maynard Keynes, Samuel Courtauld, Hindley Smith, and L. H. Myers.

At the start, when Mayor brought me into the Association, the artists belonging to it were neither young nor struggling; for instance, Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant and Keith Baynes, the foundation members, so to speak. But later on the numbers of the strugglers increased.

I think my allowance was about thirty shillings a week. The arrangement was that as one's sales increased, so would the amount of weekly payment. However my sales were never sufficient to keep me out of debt to the Association. The transactions were recorded in a monthly statement received by each member. In my statement for 1931 there is an entry relating to the sale of three pictures:

'The Restaurant' to Wilfred Evill, £31.10 [i.e. thirty guineas]. Out of this there is a Gallery commission of £6.6 and an L.A.A. commission of £3.3. leaving the artist £22.1s.

A drawing, 'Loading Ballast' to Messrs. Cooling, £7.7.0. Cooling Gallery commission £1.9.4. L.A.A. commission, 14s 8d. Credit to artist, £5.3.0.

A painting, 'the Rhine Boat,' to Miss Watts, £31.10s. Gallery commission, £6.6.0. L A.A. Commission, £3.3.0. Credit to artist, £22.1.0.

Against this there is an adverse credit balance of £63.18.5d.

From this it appears that the struggling young artist paid commission twice: to the Coolings, and to the guarantors.

To stimulate business it was decided to send Freddie Mayor to New York. But this attempt to capture the American market had poor results, apart from the sale of a couple of Duncan Grants. Soon after his return from America Mayor left the L.A.A., to start up again with a gallery of his own. We had now to advertise for a new secretary. Several young men presented themselves, but the one most suitable had a beard, and in those days anyone disguised in this way ran the risk of being called a 'Beaver'. Keynes too objected, and suggested he be informed that he could have the job on condition that he shaved his beard. Bearded or not, this second secretary did not stay long in office. The third young man to fill the post was tall, cultured and gentle-mannered, but an indifferent salesman, being more interested to sit at his desk making notes for a book on Art.

The Association rented a first floor from the Cooling brothers, who ran a Gallery of their own on the ground floor below. These Galleries were well-situated in New Bond Street, but today they no longer exist. The Coolings were two well-dressed salesman, who travelled frequently to Canada and the United States to dispose of their works of art. These were mostly small-sized highly-varnished paintings, flower pieces, Dutch interiors and landscapes. Compared to these professionals the L.A.A. were merely amateurish dealers. To reach the Associations show rooms one had to run the gauntlet of the Coolings' display of super-varnished canvasses in their ground floor gallery. These Dutchmen could prove an obstacle to the selling of the Guarantors' Cézanne school of painting.

I wonder how many collectors starting out to acquire a landscape of the sunny south of France, found themselves instead the possessor of a mist-drenched Dutch canal scene, before they could reach the stairs leading to the L.A.A. exhibition of the floor above.

As a member of the Association I had two one-man shows, in June 1929 and November 1931. Between whiles I did a portrait group of Keynes and his wife Lydia Lopokova. On a wintry Spring day, during one of the sittings, Keynes looked through the window at the sleet falling outside in Gordon Square; then briskly rubbing his hands together, remarked gleefully 'This will nip the young green shoots.' I got the impression that he foresaw a rise in the price of corn per bushel.

I continued to show work with the London Artists' Association down to 1934; about that year something happened that was to bring the Association to a stop. Concerning this, an announcement was to be made to the members, at a tea arranged by Keynes at his house in Gordon Square. Ignorant of what was in store, we sat round a table loaded with a variety of cakes, bread, butter and jam, ready to enjoy the tea. Then Samuel Courtauld, seated at the head of the table, suddenly stood up and said abruptly, 'Now that Duncan Grant has resigned I consider there is no need to continue the Association.' We sat in silence around the table; even the prospect of bread and jam with cakes to follow could not soften the jolt we had received.

But although it was the end for the other members, it was not so for me; and as Teddy Wolfe, Claude Rogers, E. du Plessis and rest of the company mournfully filed out, Keynes took me aside and informed me that he had decided to continue my allowance of £15 a month, also that he had arranged for the Lefevre Gallery to be my agents; he said it was a very good gallery, with a rich clientèle. Unlike the other dealers I had previously dealt with, Messrs. Alex. Reid and Lefevre allowed pictures to be purchased on the instalment plan; whether the 'Rich Clientèle' made use of these terms I cannot say, but I think it could be said that at least one did.

In March 1935 my first exhibition at the Lefevre was held in a small upstairs gallery, the more spacious ground floor was given over to the work of a sculptor. [Roberts seems to be mistaken here: advertisements for the Lefevre Gallery in The Times in February 1935 mention a triple bill of 'Modern French Classics', 'William Roberts: Drawings and Paintings' and 'Fergus Graham: Recent Paintings'. In March 1938 (see below) similar advertisements mention 'William Roberts: Paintings' and 'Benno Schotz: Sculpture'.] When I criticised this, Honeyman, a member of the firm, pointed out that I had the best of the arrangement, as my name was at the top of the poster advertising the show. The work sold on this occasion amounted to £240; from this the gallery took a third, while the remaining £160 went to cover the monthly sums advanced by Keynes. Three years later, in March 1938, my second and last exhibition took place. It comprised 15 paintings and 31 drawings; out of this collection 4 small drawings were sold, which brought in £70.

Following this result Keynes terminated the arrangement he had made with me and the Lefevre. According to the gallery accounts I had a debt of £318.1.1. How the 1s.1d came into it puzzles me. To liquidate this amount, Keynes took five paintings altogether. At the prices printed in the catalogue they were: Spanish Beggars, 50 gns; Shuttle Cock, 50 gns; Apple Picking, 50 gns; The Palms Foretell, 175 gns; The Tea Shop, 120 gns; making a total of £467.5.0. If the Lefevre took a third of this sum, approximately £150, as commission (unless Keynes paid them in cash) the five paintings would have to be shared between them. Furthermore it could be said that these five pictures had been acquired on the Lefevre instalment plan at so much a month.

Several weeks after this settlement had taken place, I asked the Lefevre to buy one of my drawings. I received this letter in reply from Honeyman: 'Dear Roberts, I had an opportunity of discussing with my partners the matter you raised yesterday, and I regret very much that we are not able to do anything. Our past commitments in similar directions have compelled us to abide emphatically by the rules we have laid down, and the state of business generally does not induce us to reconsider them. I will certainly do my utmost to interest people in your work, and hope that very soon a quick turn for the better will take place. Yours etc.'

And this after some four years' association with the Lefevre! At least the Coolings were ready to risk a 'fiver' on a drawing of mine. However, due to Hitler, the Lefevre directors soon discovered that as far as Art dealing was concerned, there was to be no quick turn for the better; only a very quick turn for the worse. (On this letter W.R. has written, bitterly: 'Reply to my request, first and only, that they should buy a small work, and after four years' association. What a racket!')

Keynes also 'abided emphatically' by the rules laid down for running the L.A.A. I once heard Freddie Mayor ask him for an 'advance' for a sculptor member. Keynes's comment was, referring to this sculptor, 'He's a bottomless pit.' On another occasion he remarked to me that an artist should sell his work at any price, rather than have it left on his hands. This was, he said, the method Sickert advocated. And in his article on the L.A.A. [John Maynard Keynes, 'The London Artists' Association: Its Origins and Aims', The Studio, 99 (April 1930), 235–49] he quotes Sickert as a saying 'When I get a lump sum down for a picture, it is as though someone were to pay me for my nail parings.'

In a sense, as Keynes wrote in this same article, an artist is an extraordinarily lucky person if anyone will pay him at all for products which he has probably produced mainly to please himself and as a natural emanation of his personality. Then again, as Keynes once remarked to me, 'If you give an artist money, he won't work.'

But as for Sickert, he must rarely have got a 'lump sum down' for his pictures, and was often in need of money. Eddie Marsh, who also favoured the £5 down system of picture buying, once told me that after he had collected a sum of money, to help Sickert out of his financial troubles, Sickert replied in a message: 'I suppose now you think I will change my ways. Well, I won't.' One of Sickert's expensive ways was to carry on his correspondence by means of long and wordy telegrams. I once received one of these, advising me to become a member of a new group that had just been formed called the 'East London Group.' Unlike the work of some artists, Sickert's painting was not of the elaborate kind. One can understand his being an advocate of the 'Quick Turnover' system.

Apart from Keynes, Sam Courtauld was the most active of the three remaining guarantors. But he will be best remembered, not as a guarantor of the London Artists' Association, but as the founder of the Courtauld Institute for the production of Art Gallery Curators. However, Art is not created by Curators, but by artists.

THE LEICESTER GALLERIES

The Leicester Galleries is an art-dealing business that has been carried on by two families, the Browns and the Phillips, for three generations; during most of this time in premises ideally placed for an art gallery, looking on to the trees and flower beds of Leicester Square. Furthermore, from the point of view of trade their position could hardly be bettered. The National Gallery, the Government offices in Whitehall, the aristocratic clubs round about; while across the Square the restaurants of Soho, with the right environment in which to persuade a hesitant client, or to celebrate a sale. In a corner of the Garden a few yards from the Brown and Phillips gallery, the bust of Hogarth upon his pedestal turns his back to their premises; seeming to prefer the art of the gardener to the 'Abstracts' displayed in the dealer's shop window.

On entering the gallery one is faced by a formidable turnstile in the charge of a sergeant of the Corps of Commissionaires. Having paid the entrance fee, and bought a catalogue, the visitor is now free to pass through the barrier into the gallery. This consists of two main rooms which the directors, to show that they value tradition, have named one the Reynolds room, the other the Hogarth. Brown and Phillips were always on hand to greet possible clients and important visitors.

As far as I can recollect, I first began to show at the Leicester Galleries at the termination of the first World War; probably at one of their 'Artists of Fame and Promise' yearly exhibitions. It was never clear to me, who were the artists of fame, and who the merely promising.

A star exhibitor during those years between the Wars, whose fame could not be doubted, was Nevinson. His Private Views were crowded out with all sorts of people: picture buyers and dealers, actors, men-about-town, ladies-in-waiting, art critics and newspaper-men; these last-named always on the alert for a 'Scoop'. And Nevinson, careful not to disappoint them, was ready with a stunt; like the painting that was hung covered with a sheet of brown paper, because for some reason it had been rejected by the Royal Academy. This novel way of picture presentation produced a flock of notices in the 'Dailies'.

Arriving at the Leicester Galleries one afternoon when a Nevinson Private View was in progress, there was such a crush of people inside together with a confused uproar of conversation that I decided not to wait. As I turned away I caught a glimpse of the diminutive figure of Brown in the thick of the throng; he seemed to be struggling to reach the entrance for a breath of fresh air.

Epstein was another of the Leicester's 'Best Sellers'. It was interesting to see him at one of his shows go around the gallery, sticking the red spots that signify a sale, upon his own work. Henry Moore, who had been inspecting the exhibition, remarked as he left to Brown 'Remember me to Epstein.' For me the thought of Moore being remembered to Epstein had a slight tinge of irony.

During the 1920's and '30's Max Beerbohm had several exhibitions with Brown and Phillips. At one of these a number of curious water-colours were included, that could be termed 'Puzzle-Pictures'. They consisted of square pieces of paper, splashed and smeared with paint and then framed. The effect, it seems, was got by dropping blobs of different colours in the centre of a piece of paper, this was then folded into four and then pressed; when opened out it resembled an 'Action' painting in miniature. Although the Leicester had two shows of these 'Abstracts', Max Beerbohm did not succeed in founding a 'Max-ist' group. But one could say that in the '30's they were the fore-runners of the 'Actionist' paint slingers of the '50's.

One of the Leicester Galleries' favourite exhibitors, and a painter of splashes and smudges in the grand manner, was Ivon Hitchens. He had a patron, a wealthy composer of music and an enthusiastic collector of Ivon's Abstracts, who once said that when he was tired of looking at them one way, he got fresh enjoyment by hanging them upside down; two for the price of one, it would seem.

Midway in the 1930's, an artist of dynamic personality, David Bomberg by name, had an exhibition at the Leicester of work he had done in Palestine and Arabia. During his stay in the Middle East Bomberg made the acquaintance of Sir Ronald Storrs, who had helped him and his wife in their travels, by procuring for them camels and an Arab bodyguard. Bomberg told me in his modest way, that the Arabs thought more of him than they did of Lawrence. However, in spite of his assurance, I don't think Bomberg would have made a very suitable 'Uncrowned King of Arabia' even with the help of Arab costume. It was not Zionism or an Israeli State either, that interested him, but Communism. He had visited Russia; and was for a time active in the 'Party,' addressing meetings from a platform at street corners in various districts of London. Storrs was interested in Bomberg's work and wrote an introduction to the Leicester Galleries' show, in which he asked Brown to 'Please send us back our Bombergs', a request that much amused the Directors.

I had little to do with the Leicester during the later years of the Thirties as I was then a member of the London Artists' Association, and after that under contract to the Lefevre Gallery. Then in 1939 came the conflict with Hitler and the Nazis. I recall a visit I made to the Leicester Galleries one morning in the early part of the war; there had been an air raid the night before and the gallery had been damaged. I found Brown and his assistants putting things in order and sweeping up broken glass. He said to me 'We don't intend to close, Sir Kenneth Clark has asked us to carry on.'

During the Hitler War, as a part-time Official Artist I did a couple of paintings and some drawings for the Ministry of Information; but nothing in the Grand Style of the First World War.

In 1945 at the War's end I had my first One-Man show at the Leicester. I shared the Gallery with Henry Lamb, A.R.A., and Dora Gordine, a sculptress. Of the 25 drawings exhibited I sold 8 and this detail is the only record I have of the event. Four years later I again showed a collection of water-colour drawings, 29 in all; about 10 of these found purchasers. After deduction of gallery commission, namely 33 1/3%, the amount to me was £181. 10s, and from this sum had to be subtracted the cost of framing.

After a period of nine years, in February 1958 I had my last exhibition at the Leicester; this comprised paintings as well as drawings, among them several lent by their owners. One drawing 'The Horse Dealers' priced at £25, was sold to Freddie Mayor at a reduced sum; because, as Brown explained to me afterwards, 'Mayor is a dealer.' However, Freddie lost no time in selling it almost immediately to the Tate Gallery at much more than the 'Cut Price' he paid for it.

One afternoon during the show Brown, myself, and Ernest Cooper the owner of the work, were standing before my painting 'The Rape of the Sabines'. After a while, Cooper remarked to Brown, 'I am asking £750 for that Roberts.' Brown looked at him sceptically and said 'He won't get those prices, not in my time.' An expression of opinion that would hardly give a struggling artist much confidence in Brown's salesmanship.

A standing complaint of my wife against the Leicester Directors was that they would not display a work of mine in their window; although it was customary to do so when an artist had a one-man exhibition. I could understand her resentment on seeing a window display of the work of some other artist, whilst a Roberts show was taking place inside.

One day in the late 'Thirties' I received a letter from Eric Kennington, who wrote that he had taken my drawings for the tail-pieces of Lawrence's Seven Pillars of Wisdom to the Leicester Galleries and given them to Brown. He explained that he had done this because 'Lawrence doesn't keep things', but added that if I wanted the drawings I should go and ask Brown for them. This I did. However at first Brown seemed reluctant to part with the tail-pieces; and it was only after several requests that I got possession of them.

After my election to the Royal Academy in May 1958 I ceased to exhibit at the galleries of private dealers, and it was not until 1970 that I began again to do so. Some time during this interval of twelve years the Leicester had vacated their old premises in the Square; as to when this move was made, and to where, they gave me no information.

THE REDFERN GALLERY AND REX NAN KIVELL

Another Gallery besides the Leicester, that after the last war could have hung out a 'We never closed' sign, was the Redfern. In 1942 through the intermediary of a friend I made the acquaintance of Rex Nan Kivell, an Australian [in fact a New Zealander] and the Director of the Redfern Gallery. As a result, in July of that year I had an exhibition at the Redfern.

It was not exactly the best time to have a show of pictures, during the 'Battle of Britain' and nightly air raids on London. Certainly it would not have occurred to me to do so but for the insistence of this friend, that I should make use – even under war conditions – of any publicity I could get. However, if the event caused no public commotion, the financial result was not a sensational event either. Out of 18 oils and 23 drawings, 3 paintings and 4 drawings were sold, amounting to £133.2.6. This sum was paid to me by Nan Kivell in four instalments: 5th Oct. 1942, £50; 26th Oct., £25; 13th Nov., £25; 7th Jan., £33.2.6. Still, considering the state of the times, I was perhaps lucky to sell anything.

It was an empty London, patrolled mostly by air raid wardens and the Fire Brigades, who for relaxation between raids whiled away the time playing darts. But Nan Kivell had other resources than darts, to ease the strain of living in a bombed city; there was this book on Art, that he had been working on for years, which according to his secretary he would never finish. Also there was at 20 Cork Street a basement gallery that could be used at night for soirées, and as a meeting place for those interested in Art, besides the many artists in the Warden and Auxiliary Fire Services. Members of the theatrical profession were also visitors to the Redfern, and not always as buyers; sometimes when engagements are scarce an actor may be compelled to sell one of his 'Old Masters' or other Objet d'Art. Some dealers might prefer to do business with a hard-up actor or film actress, than with a hard-up artist.

An Art Dealer once told me that transactions with artists, or people with pictures to sell, were difficult and troublesome; Art Dealers, he said, preferred much more to do business among themselves. The activities of the Dealer take place in his bright and tastefully arranged gallery, among a constantly changing flow of visitors, whose preferences cause his sales talk to adapt itself to their tastes. Into this animated scene comes the artist with his bits of colour-daubed canvas to sell. He has no high rent or overheads, and most likely spends his time painting in a dingy room. It was a room of this sort that caused a wealthy art patron to remark, after visiting, 'I hate squalor.'

At the one-man exhibitions prices are rarely printed in the gallery catalogue, as this would hinder the dealer's freedom to bargain. Consequently the purchaser does not know what the artist is asking, nor does the artist know what sum, above his own price, the dealer is getting. He only knows he must pay a third of his own price to the dealer when a sale takes place. The dealer endeavours to persuade the artist that he is doing him a service by forcing up his prices, although actually he gets nothing from these increases.

Some years ago I sold a painting for £100, which recently fetched £8,000 for its owner, in the sale room. It is true the price has gone up, but it is the owner who benefits, not me.

Around the year 1900 the art dealers' shops in London could be counted on the fingers of one hand; at the present time their number is nearer a hundred. In the vicinity of Bond Street, the traditional home of the Art Dealer, there is a small street that has in it ten dealers' galleries. Their names are: the Piccadilly, Roland Browse and Delbanco, The Cork Street, John Wibley, Leicester, Mercury, Hamet, Sabin, and three Waddington Galleries. What a commotion there would be if they ever had their Private Views at the same time!

It is now fashionable to have these functions in the evening, when the artist and his work are launched on a flood of cocktails and champagne. Back in the more sober years of the mid-thirties I visited a gallery in the neighbourhood of Hanover Square, where a friend was having an exhibition. There were only two people in the gallery, the dealer and a well-known art critic; the critic, referring to the artist whose work was on view, said to the dealer 'He is a young man with a brilliant future behind him.' The art dealer laughed, and seemed in full agreement with this eminent art critic's judgement. This was hardly, I thought, the spirit in which to promote the sale of my friend's work.

Dealers adopt a very kindly attitude to the critics and newspaper reporters; for a good display of notices in the Press can boost an exhibition and bring in the collectors. On their side, the gentlemen of the Press appreciate these Private Views with their champagne, cocktails and nuts; finding maybe with these stimulants their critical faculties enhanced.

I remember Sir Henry Rushbury R.A. at one of the Academy's General Assemblies, complained that at the Members' Summer Exhibition Press Day, the reporters never got beyond the first room, where the cold buffet and drinks had been arranged for them. 'It has always been so,' he said, 'and always will be so.'

As to the Redfern Gallery, after my 1942 show I had no further business with it. At some date between the end of the last war and the present time Rex Nan Kivell retired from Art dealing and settled in Morocco; where perhaps aided by the stimulating warmth of the African sun, visits to the Kasbah, and camel rides, he will be able to finish that long-contemplated book on Art at last.

January 31st 1973

(Note: the painting which fetched £8,000 – at Sotheby's on November 22nd 1972 – was 'Bank Holiday in the Park'. According to Sarah this picture was sold for £30 to Eric Kennington, who later gave it back. Still later it was bought by the patron [Ernest Cooper], who told me that it was rolled up on the floor of the studio, and that he gave the price asked – £100.

I have the catalogue of this sale, with Sarah's notes on some prices. I can still remember W.R.'s look of stupefaction when she told him of the price fetched by 'Bank Holiday in the Park'.

J. D. R.)

News | Gallery | Auction results | The artist's house | Contact

List of works illustrated on the site

Catalogue raisonné:

chronological | alphabetical