AN ENGLISH CUBIST

WILLIAM ROBERTS:

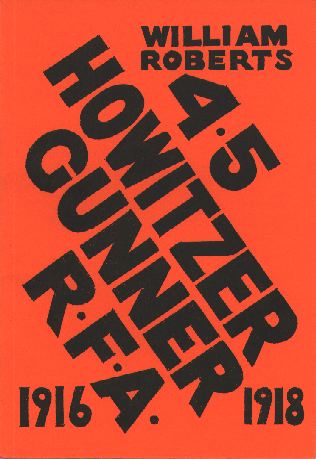

4.5 Howitzer Gunner

Royal Field Artillery

1916–1918

Memories of the War to End War

1914–1918

This piece was first published (London, 1974) as Memories of the War to End War 1914–18 (on the title page) or 4.5 Howitzer Gunner R.F.A. 1916–1918 (on the cover) – 'one of the finest war books I have ever read', A. J. P. Taylor, London Review of Books, 6 Dec. 1984. The present text and title are taken from William Roberts, Five Posthumous Essays and Other Writings (Valencia, 1990). © The Estate of John David Roberts.

4.5 Howitzer (oil on canvas), c.1924

© The Estate of John David Roberts

When the war began in August 1914, I was living in a room at Chalcot Crescent, Chalk Farm, and fellow artist David Bomberg had a room on the corner of St George's Square nearby. Also in the neighbourhood were several other ex-Slade students, including B. Meninsky and Geoff. Nelson. The first three months of the war were particularly difficult for us. Money was conspicuous by its absence, for there were no student's grants in those days.

In this situation of penury, Bomberg wrote to Lady Ottoline Morrell and the Artists Benevolent Fund, but without result. My effort was to call on Augustus John at his house in Chelsea. It was a winter evening, and the spacious studio was unlit save by a wood fire in a large open grate. We sat in silence facing each other beside the fire, I hesitating to reveal the purpose of my visit. Finally, John got up saying he had to go out.

Together we left the house and walked along the King's Road toward the Six Bells. As he was about to enter the pub, John handed me half a crown. This result was as disastrous as Bomberg's had been. The sight, as I reached Piccadilly, of a Red Cross ambulance filled with wounded 'Tommies' put the finishing touch to this rainy night's adventure.

Despite Lord Kitchener's image with its commanding finger pointing down from the hoardings, during most of 1915 I paid more attention to matters of art and picture-making (as did most of the artists with whom I associated) than to the war taking place in France. I produced a cubist St. George for the 'Evening News', some drawings for the 'Second Blast', a number of paintings for the Vorticist show at the Doré Gallery, and some for the London Group at the Goupil. Besides this, and in a rather different sphere, I worked some weeks making bomb parts in a Tufnell Park munitions factory. But civilian life was becoming more difficult as 1915 moved to its end. Upon the hoardings, replacing Kitchener, a new figure appeared: Lord Derby, a civilian. He had a scheme to offer that in one way could be attractive to potential recruits. All they need do was to go to a recruiting office and sign a form, then return home and continue with their usual occupation, even perhaps forget the incident. However, the military remembered, and one fine morning the postman dropped a call-up notice into the letter-box, and then it was goodbye to civvy life for the duration.

By the beginning of 1916 most of my artist acquaintances had joined the Derbys. Lewis had put on a heavy pair of hiker's boots and had gone off to 'Blast and Bombard' in the Garrison Artillery. Myself, having failed to get accepted by the Artist Rifles, tried on Lewis's advice to enlist in the Welch Regiment whose Colonel was Ford-Madox-Hueffer. Fortunately for me, this attempt was unsuccessful too. However, when attesting at the beginning of March 1916, I said to the sergeant signing on the recruits, 'I want to join the Welch Regiment', he looked at me and replied in a brisk soldierly voice, 'Sorry lad, join the Field Artillery and wear spurs.'

About a month after this, on 4 April 1916, I received my 'call-up'. So for the next three years I was to be No. 123744, a gunner in the Royal Field Artillery.

On the following day at 9-30 am I joined a crowd of recruits on Horse Guards Parade assembled for dispatch to their units. Also on the parade ground was a company of the Guards marching to and fro to the stirring music of the drums and fifes, their rifles at the slope with fixed bayonets glistening in the sun of the spring morning. This martial scene was intended, no doubt, to be an appropriate send-off to our military careers. My next move was to report to the officer commanding the 4th Depot RFA at Woolwich. Here I received a khaki uniform and spurs, together with other bits of equipment, such as button-stick, holdall, and a burnisher for my spurs.

The day started with reveille at 6 am when we groomed, watered, and fed the horses – the animals were always attended to first. Besides this, there were cookhouse fatigues, dish-washing, and sacks of potatoes to be peeled. These jobs were varied with a little route marching, ending usually in a sit-down and a smoke. The sergeants were not fond of route marches. One afternoon we had a lecture by a young officer on the care of the feet. Most of the audience were not interested in their feet and fell asleep. When the barrack chores were finished, a stroll round Beresford Square – to display our new uniforms – ending with a visit to the 'boozer', made a pleasant end to the day.

At the Woolwich Depot the recruits were housed in small rooms that had formerly been married quarters. There were two or three beds to a room, but not beds of the conventional type, they consisted of three planks that could be placed on two low trestles about 6 inches from the floor. These low beds were useful at times; at night when one of the occupants who had taken too much liquor, rather than get up, would prefer to relieve himself from his bed, resulting in a good deal of urine over the floor, and splashes on the walls.

After being vaccinated, we recruits were transferred to a cavalry barracks at Weedon near Northampton. Here we stayed for the next five months doing gun drill on eighteen pounders, until in August we left for Woolwich on our way to France. During our training at Weedon, the day began at reveille, when we raced down to the canteen to snatch a quick cup of tea before stable parade. An hour was then spent grooming the horses. This done, they were taken to the watering troughs close by and then brought back to their stalls again; they waited impatiently to be fed. This was done in true military fashion. On the order 'feeds round', each man would collect from the stable orderly a bucket of chaff and oats, placing it behind his horse. This caused a good deal of prancing and kicking among the animals, who were only separated from each other by a thin pole; for although they faced the wall and their mangers, the horses were fully aware of what was happening at the rear. After 'feeds round', the next order was 'feed'. At this the men standing behind the restive horses seized their buckets and darted quickly between the animals to empty the food into the mangers, getting away as fast as possible to avoid any sudden kicks. Speed was the essence of the manoeuvre. The horses watered and fed, we were then free to go to our own breakfast.

This was followed by a strenuous session of buttons, boots and spurs polishing in preparation for the morning parade on the barrack square. With the men lined up and the sergeants slightly in advance of their subsections, the sergeant-major, accompanied by the duty officer, took up a position in the centre of the square. The sergeant-major then called 'Number ones', and the sergeants doubled forward and took up a position in line before him. Standing to attention, they received their orders for the day, whereupon they doubled back to their men, and the parade was dismissed.

Apart from fatigues such as scrubbing the barrack-room floors with brick dust, unloading and carrying large sides of meat to the cook-house, besides kit inspection, the gunners' chief occupation was gun drill. This took place on the parade ground, and consisted in gun-laying and rehearsing at the double, the positions to be taken when firing the piece. But this last part of the business was postponed until we arrived in France.

At night, most of the men when not on guard duty passed their time in the village pubs. For their use on returning to barracks, having imbibed not wisely but too well, large wooden tubs were placed on the landings outside each barrack-room door. Before morning these tubs would be full to overflowing. The job of emptying these receptacles did not inspire the fatigue parties with much enthusiasm. For those who preferred to pass the evening in barracks, there was crown and anchor played on the square or a foursome at cards played on the bed of the one who owned the pack. But when 'lights out' was called at ten o'clock, the game was continued in the glimmering light of a candle end. Occasionally, pastimes were more vigorous, when some unpopular character was tossed in a blanket.

Among any group of soldiers one finds a lead-swinger or an 'old-sweat' or two. In our dormitory 'Jock' seemed to combine both these roles. 'Jock' was a regular and it was said he had been in the retreat from Mons. From 'Jock's' behaviour there must have been devils as well as angels there. He was subject to fits of fury. Usually these would happen at night. When we were in bed and half asleep, suddenly there would be a shouting and a banging coming from 'Jock's' bed. Immediately several men from neighbouring beds would leap on him and forcibly hold him down. Poor 'Jock'. All this racket, while disturbing our rest, at the same time aroused our sympathy, until one night during a bout of his fury, in the scuffle that went on in the dark, the sound of chuckles and suppressed laughter made one suspect that the only spirits that upset 'Jock' were those at the 'boozer'.

From time to time we had to take turns at guard duty. On these occasions we were lodged in the guardroom for forty-eight hours, each man of the party doing two hours on sentry-go and four hours off. During their rest period the men had to remain in the guard house. At night we challenged anyone approaching our post with 'Halt, who goes there?', the usual answer being 'Friend'. We would reply 'Pass friend'. But the retort to our challenge would sometimes be 'Officer visiting rounds', in this case the reply would be 'Pass officer visiting rounds'.

Besides this traditional guard duty there was a more modern one. This was the period of the Zeppelin raids over England, and to show that they were fully aware of this danger from the sky, the barrack command organized its own anti-aircraft defence. In a field about half a mile from the barracks, a round shallow hole was dug large enough to take an eighteen-pounder gun with its barrel pointing as far as it was able to the sky. In this awkward position, this low-trajectory gun could not possibly have been fired at anything directly above it. Still, it served to give an extra guard duty posting sentries with rifles but no ammunition, wearing bandoliers whose pouches were stuffed with paper instead of bullets to watch over a field gun masquerading as an anti-aircraft weapon.

In barracks the great day was Sunday. This meant morning church parade, with the whole barrack-load of artillery-men, bandoliers, buttons, and spurs brightly polished, headed by the regimental band, on the march through the village of Weedon en route for the church. During one of these church attendances, the officer in charge sitting in a front row pew being of the opinion that the sermon was becoming too drawn out, signalled to the young chaplain conducting the service to cut the sermon short. The officer got his message over by a kind of semaphore movement with his wrist watch. Parade over, lunch over, the men were free for the rest of the day.

On one of these Sunday afternoons, whilst taking a walk in the village of Weedon, I came upon an attractive-looking inn. As it was near tea time, I entered. In an empty dining room upstairs there was a waitress who seemed to be waiting for a possible customer. After finishing my tea of toasted scones and jam, I left, and so far no other patron had appeared. I vowed to visit this inn again on my next afternoon off. The following day I seemed to be a subject of special interest for all the other inmates of the dormitory. From their sarcastic remarks and jibes I learned that this inn was for officers only, and was out of bounds for non-commissioned officers and men. For the rest of my stay at Weedon barracks, I took my Sunday teas in the NAAFI canteen.

Perhaps it was the thought of this forbidden inn, I don't know, or maybe it was incitement from some of my roommates that made me decide to apply for a commission. Having been granted an interview by the commanding officer, I found him in a rather gloomy room seated at a large table and myself standing to attention before him at the opposite side of the table with my escort close behind. After his first few questions, I, seeking to make the interrogation less formal and myself more at ease, rested my hands on the edge of the table. Immediately there came a terrific explosion that caught me full in the face leaving me dazed. At the same time, from across the table, I heard a voice yell 'Stand to attention man when you address an officer.' I was then promptly dismissed. As I left the room I realized that any hope of taking tea with the officers at the inn had gone.

For the next few months, tending and grooming the horses and gun drill at the double on the barrack square was our daily routine until the beginning of August, when I was picked for the draft to go overseas. The few days of my overseas leave I spent at the Eiffel Tower Hotel, when this was over, I reported to the RFA depot at Woolwich. In mid August, we entrained for Southampton and crossed the Channel at night, reaching Le Havre in the early afternoon. Leaving the docks, we marched to our encampment past a group of hospital huts, where some of the convalescent wounded in their blue suits lined the route and gave us an encouraging cheer.

This first night in France was spent without much sleep in an open field under the sparse cover of a hedge. But earlier I had paid a visit to a nearby 'estaminet' packed with a noisy crowd of beer swigging 'Tommies'. I left, finding it impossible to keep pace with their drinking, and returned to the open field seeking shelter and warmth, with the aid of a blanket, under a hedge. But with the arrival of the boisterous group of overloaded drinkers from the 'estaminet' looking for bed-space, sleep was out of the question.

The next morning our journey to the line was continued by rail in wagons that could be used either by men or horses as the occasion required. After a short halt at Rouen, we journeyed on to Poperinghe, and from there to the supply column of the 51st Brigade RFA attached to the 9th Scottish Division.

We reinforcements were then subjected to a sorting out process, some going on to join the batteries, while others remained for a course of signalling. I was included in this second group. Our tutor was a sergeant who was not too exacting in his instruction. In the mornings we would go to an empty barn and practice the Morse Code on an instrument called the buzzer. In the afternoon we split up into groups and from various points, by the use of flags, sent messages to each other in semaphore. This flag-waving was a stimulating exercise, but it was never used by us when in action.

After a week or so of this pastime, we left this quiet village to join our batteries of the 51st Brigade 9th Division. The infantry of the division was composed of Scottish regiments drawn from England, Canada, and South Africa, but to us they were all 'Jocks'. D. Battery, to which I had been allocated, consisted of six 4.5 field howitzers, and was commanded by Captain Delahaye.

The battery, well dug in, was in position facing Vimy Ridge and our infantry entrenched just below the crest. I had joined the battery with two companions, an Irishman named Kelly, and a cockney whose name I forget.

My first warlike encounter at the front, was not with the Germans but with the Irish. Kelly had taken a dislike to me, and one day came at me with his jack-knife. I stood back and said 'You wouldn't be so bold without your knife.' He immediately put his knife away and stuck up his fists. However, as I made no attempt to adopt a similar pose, Kelly waited motionless for a moment in a sparring attitude, then with a glance of contempt in my direction, and a muttered 'Jesus Christ' went back to delousing himself. Shortly after this incident Kelly was transferred to another battery, and many months passed before I saw him again.

We new arrivals paid our first visit to the trenches in the company of some more experienced signallers on an inspection and repair tour of our telephone wires. As we struggled carrying our phone equipment through a narrow communication trench, we got held up by some wounded on stretchers being brought down from the front line. Further along the trench we came upon two 'Jock' officers sprawled on their stomachs upon the chalk mound above the trench, who were observing the distant ridge through field glasses, offering to us at the same time a view of two pairs of thighs below their crumpled kilts. The smartness and sparkle of their uniforms and Sam-Brownes showed them to be recent arrivals to the trenches. In passing, I detected a faint aroma of perfume. The track of our wires led us past a dressing station dug-out cut into the hill-side. A 'Tommy' carrying a wounded man upon his back staggered toward the entrance. The casualty had the bright end of a rifle bullet protruding from the back of his bare thigh. Moving higher up the ridge, we came upon the ruins of an old church and cemetery whose vaults had been used as shelters by the 'Poilus' when they had occupied this part of the line.

At the start of our cable inspection the party had split into two groups, and although we had made the round without hurt, the other lot had not been so lucky. One of its members, the cockney on his first day out, had got badly wounded, and could not return to the battery.

An important part of a signaller's work is to see that contact is kept between the batteries, and also with the headquarters of the brigade; in addition there is the wire to the artillery observation post in the front line. The infantry also had their telephone cables. These thin insulated cables of different colours, with their identity tags, crisscrossed the ground in all directions. They were continually getting broken or cut by shell bursts. When this happened, the line was said to be 'diss', and this meant signallers turning out. Putting the broken ends together again was hard enough in daylight, especially with 'Jerry's' shells dropping around. However, it was far worse to leave your dug-out at night and grope about in shell craters and mud, searching for the damaged wires with the 'D Battery 51st Brigade' label attached, while the enemy's guns did their best to destroy them again.

Toward the end of 1916, our battery moved to the Ypres sector. At the same time we took on a new commander, Major Morrison. He was a tall, handsome, square-jawed man, very alert, every inch a regular soldier. It was the rule that the Major should be with the guns while the second-in-command, the Captain, would have control of the wagon lines. In our battery this position was held by Captain Logan, an officer who was very particular as to the smartness of his personal appearance. Due to the skill of his batman the Captain's Sam-Browne and jackboots always had a mirror-like sparkle and brilliance that was the envy of the other officers and their batmen. It was true he seldom had need to put his feet to the ground, preferring as a rule to be mounted, seated well above the mire, upon a horse whose saddle and harness were as brilliant as his own equipment.

Mud there was in plenty around the horse lines and watering trough; the animals waded knee deep in it. This made the grooming process hard work for the drivers. There was one little shaggy black horse named Kaffir that it was impossible to clean. He had, understandably, been abandoned by the 'Bosch' and we had adopted him as a kind of mascot. There had been unsuccessful attempts to groom him, but nobody dare touch his hindquarters. One man had tried it, only to receive a kick in the face which sent him to hospital and left the permanent imprint of Kaffir's shoe upon his cheek. So Kaffir was neglected, his tail grew long and collected much mud, which slowly formed into a large hard ball, and this as the animal moved swung between his hind legs in a very ludicrous fashion.

Another well-polished figure at the wagon lines was Sergeant-Major (Spud) Murphy (in the army all Murphys are Spuds, just as all Clarks are Nobbys). Murphy was a disciplinarian, consequently not very popular with the men, and there were muttered threats from some of them as to what they would do to Spud if ever they met him when the war was ended.

Captain Logan's polished jackboots were of some concern to me because for a time I was batman to an officer of my subsection, Lieutenant Duthey [probably Lieutenant R. E. A. Duthy of the 51st Brigade, RFA], who, although I failed to get the same shine on his boots as Logan's had, did not appear to be unduly concerned about it, for when he went for a week's rest to Paris-Plage, a peace-time seaside resort near Boulogne, I accompanied him in my role as servant. This stay by the sea was a refreshing change from the battery dug-outs. When not engaged in polishing the officer's buttons and brushing his tunics, I spent my free time reading Flaubert's 'Salammbo' in an English translation. It was winter and the sea looked monotonous and grey. The town seemed abandoned, the only sign of life I recall from my visit there was the sight of two Portuguese officers walking together wrapped in their long grey-green cloaks along a deserted wind-swept promenade. My career as a batman came to a sudden end shortly after our return to the battery. Difficulties arose when Duthey asked me to cook him an occasional meal. At this period we were under canvas at the wagon lines. One morning he ordered a welsh rabbit for breakfast. My kitchen was close by Duthey's tent in the open air, and consisted of a hole in the ground into which I had placed a large round metal can, open at one end, to serve as an oven. A wood fire under the can burned well, so into the oven went some cheese on a piece of toast to melt. When it seemed to be ready for eating, I took it to the officer's tent, placed it on his camp table, and left. I had not gone far when a loud yell of 'Roberts' came from the tent. Returning, I found the lieutenant holding upon the end of his fork a large solid piece of cheese, having the consistency of stone, that had become detached from its slice of toast. Duthey was not prepared to try any more of my cooking experiments so I returned to ordinary duty, and he searched around for another batman.

His second choice was more successful; he found a gunner who in civvy life had been a man-servant to a wealthy family, and also knew the routine of the kitchen. I had often heard this chap talk of the good times he had enjoyed in his job, especially with the chambermaids. He and a gunner named Chalky, who had been a coalman before joining the army, liked to reminisce about their pre-war amorous adventures. It often happened that Chalky, after delivering a load of coal to some mansion, would be invited to partake of a cup of tea with the cook in the kitchen. It was left to his audience to guess what that cup of tea implied. Once on returning from leave, he told us he found an ordinary bed so comfortable he couldn't sleep in it, so got out and slept on the floor.

There was also a third Don Juan known in the battery as 'Cockney' Sharpe who liked to relate his past 'affairs' with women, but these seemed to be mostly prostitutes. Cockney had been a boxer and came from Bethnal Green, a quarter of London renowned for its boxing champions. Besides boxing, he liked to sing, and from time to time would start up with a few lines of a queer refrain that had a beginning but no end, thus:

I had a dream last night,Having got so far, he would stop and start again. Cockney got as much pleasure from this fragment as the others did from 'Mademoiselle from Armentières'. Perhaps it helped him to endure the strain of the war. During the battle of Arras I lost touch with Cockney and his dancing devils.

I had a terrible fright,

I dreamt I was with the devil below,

dancing at the devil's,

Oh you lucky devil,

dancing at the devil's ball.

However, there were some who were not inclined to sing their troubles away. The Limber-gunner of my subsection once confided to me that he was so anxious to get away from the fighting, he put his foot under the moving wheel of the gun-carriage, but to his surprise it suffered no damage. The ground being soft, his foot was just pressed into it. He had also tried sniffing gas shells, likewise without success.

Still, being at the 'Front' had certain compensations. It became the custom among the girls in the munition factories, when packing the shells into boxes, to sometimes put their names and addresses or a photograph of themselves with a note inviting a reply. For the 'Tommies' who did so, there was the likelihood of a stimulating correspondence, cigarettes, or a parcel of food, and who knows what else besides. But sometimes, besides the 'billets-doux' there would be in the box of ammo a defective shell which could cause a 'premature', that is to say, when it was loaded into the gun and the gun was fired it would burst in the barrel. This happened to one of our battery's guns, during night firing on the Somme. Fortunately the crew escaped injury.

From Ypres in the early spring of 1917 the 51st Brigade moved to Arras. Here, men drawn from D. Battery and the other batteries of the brigade, were formed into working parties whose job was to dig gun-pits. We were billeted away from the battery in some empty houses that had been abandoned by their former occupants. Our first task was to make concealed gun emplacements inside a row of ruined villas, in a street with several dead horses lying about, the remains of some convoy caught in the enemy bombardment. From our billets, on the march through the deserted town, our route led past a large uninhabited convent. This soon became the target for those of us with a taste for souvenir hunting. Inside all was confusion indicating either a very hurried departure of the nuns, or that other collectors had been here before us. However, a quick survey of the interior sufficed me. I felt the place and the time were not right to go searching for mementos.

In addition to the work that was done in Arras, we made a number of gun-pits close behind the front line, and these were carefully covered with camouflage to conceal them from the Bosch observers until our batteries were ready to occupy them. When this preparatory digging was finished, we were employed in the vacant offices of the 'Mairie' making camouflage screens. This consisted in tying strips of various coloured bits of canvas to string netting, or painting large spreads of canvas with jig-saw patterns. These we took at night and hung on trees or wood supports, the intention being to hide from the Germans a portion of road which would be used by our guns and transport in the event of an advance. But whether the enemy were deceived by this contour that had arisen overnight, there was no means of knowing.

We had not been at work many days on our camouflage, when an officer of the Engineers arrived at the 'Mairie' to inspect our work. I recognized in this 'expert' a fellow student of my Slade days, Colin Gill. Here was my chance of a transfer to the camouflage section, but I hesitated to introduce myself, and before I could decide he had left. However, I vowed that on his next visit I would make myself known. Alas, the opportunity did not occur again. Some days later, another inspection officer turned up at the 'Mairie'. He too I had known in pre-war times, Leon Underwood. He seemed agitated, wore his tin hat tilted forward in a comic fashion, and there was a drip at the tip of his nose. He demonstrated how the strips of canvas should be attached to the netting, then hurried away. On this occasion I made no attempt to be recognized.

With the preparations for the Arras attack completed, the artillery working parties were disbanded and rejoined their batteries. Following the infantry advance, D. Battery began to move forward at night. As we passed through the village of St Catherine, the heavy guns and howitzers of our garrison artillery, firing almost wheel to wheel, filled the night with their deafening, blasts, pounding the Bosch trenches and rear. The road we were on was congested with vehicles trying to move in opposite directions; batteries and supply wagons, lorries carrying troops moving up to the fighting line, ambulances filled with wounded coming away from it. Once we were held up while some wounded were being transferred from one ambulance to another, and other wounded on stretchers placed on the ground awaiting their turn to be reloaded, blocked all movement of traffic. In addition the continual flashes of gun fire and the distant rumble of the bombardment up ahead increased the mood of depression caused by this chaotic night scene.

Continuing our journey forward, we came upon an unexpected sight. Dotted around over a wide area were numerous blazing wood fires and grouped about them were parties of cavalry-men with their horses. The ground at this place had been laid out with guide-lines of white tape to indicate a path through the barbed-wire and shell craters that the cavalry were to take when they made their break-through attempt. But our infantry were held up by the 'Bosch', and the plan was not carried out.

When dawn came the cavalry had already disappeared leaving behind them the white guide tapes on the muddy ground.

As we moved towards our new position, the German artillery began to send over some nasty black bursts of shrapnel which exploded with a sickening crump above a column of infantry moving up to the trenches in single file on a duck-board track. From time to time, when someone in the file was hit, there was a cry of 'Stretcher-bearer'. Meanwhile, the rest, without pausing continued on their way to the front line.

Our battery column came finally to a halt and took up a position facing an escarpment. Taking into consideration the high angle of fire of our 4.5 howitzers, we would be able to bombard the 'Bosch' from the shelter of the high ground, so we set about making ourselves comfortable. We planned to make several deep dug-outs, after the German fashion, and employed our spare time tunnelling obliquely through the hard chalk earth. These shafts, when deep enough, were to be connected and formed into comfortable shelters. Some months later on the Somme I was able to explore a deep dug-out that had been abandoned by the Germans. A deep wood-lined stairway led down to several rooms that were also lined with stained wood. Some furniture still remained, a large table and some chairs. However, our own diggings at Arras were brought to a sudden stop when we had gone down about 15 feet. For this position, which seemed to be sheltered by the cliff, could be enfiladed by the German batteries.

This may not have been the reason for leaving our half-made dug-outs, but in two days we had two men killed. One was tall, gaunt Tom Gunn, the Limber-gunner of F. Sub-section. As we stood by his corpse someone lifted the blanket that covered his face. It was emaciated and the colour of pale ivory. The other man had died from shell shock. He stood upright by the wheel of his gun unmarked but quite dead. Just a short while before he had invited some of us to share in a parcel of food he had just received from home, but the party had to be cancelled.

On the way forward to our new position we saw several dead infantry-men. One in particular I remember whose arm was separated from his body and lay a yard or so from it.

A more exposed site on higher ground had been chosen on which to place the battery. We started immediately to dig pits for the howitzers, in haste to get finished before nightfall. They would, besides, serve as shelters for us should 'Jerry' begin 'strafing'. 'Jerry' was one of the names we gave the Germans. We used others according to our mood such as 'those square-headed bastards', and bastards they surely were. On that first night when they bombarded us with 'Wizz-bangs' and gas shells, I spent the night in the shelter of the gun-pit under cover of a tarpaulin wrapped in my blanket and without a gas mask, listening to the thud, thud of those gas shells hitting the ground above. The nozzle of these small projectiles came off on impact and a quantity of gas was emitted. If they had little effect upon us, they did considerable damage to the cook's stores, destroying our bread, bacon, and tea rations, leaving us for the following day only our iron rations, that is the tin of bully beef and some biscuits that each man carries for use in an emergency.

On the left of our position were some French batteries of 75s; these field guns are similar to our eighteen pounders, but have a much more rapid fire and an earsplitting crack with each round. These French neighbours were in continuous action, making such a racket that the Germans must have discovered their position, or so it would seem, for after a while their artillery began to reply, and unluckily we did not escape this return fire. One night A. Sub-section's gun-pit received a direct hit that blew up the gun, its crew, and Corporal Garrity the No. 1, who were sheltering there. One incident I especially remember of that hectic night, is the picture of Major Morrison on his hands and knees among the ruins searching by candlelight for survivors. We buried our own dead, together with some left over from the infantry's advance, shoulder to shoulder in a wide shallow grave, each in his blood-stained uniform and covered by a blanket. I noticed that some feet projected beyond the covering, showing that they had died with their boots on, in some cases with their spurs on too.

The Arras battle had been brought to a standstill. And in the late autumn of 1917 the 51st Brigade were in the Ypres sector, north of the Menin Road. I recall about this time several sorties we made on telephone-wire repairing expeditions. On one of these, carried out at night, we came upon a party of 'Jock' infantry standing in the shadow of a ruined barn blacking their faces, preparing to make a raid on the German trenches. Up ahead at the front line a trench mortar bombardment was going on, filling the night with a continuous thunder turning the horizon into a blazing line of flame and smoke. I did not envy these 'Jocks' their task and was thankful our job did not take us that far.

Later, I was detailed together with some other men and an NCO, to make a night journey taking three wagons of ammunition from the wagon lines to the battery. After travelling a couple of miles the track we had been following gave out; there appeared to be nothing ahead in the darkness but broken ground and shell holes. In this fix, the sergeant-in-charge called a halt. To make the situation worse 'Jerry' began to drop shells round about, some coming uncomfortably near to us. This started a panic among the horses causing them to rear and neigh with fear. It was a struggle to keep them under control. A few yards away on our left there was a faint glimmer of light. We found it came from a hole in the ground partly covered with some cupolas, and lighted by two pieces of candle; squatting inside were two Australian 'Tommies' having a meal of pork and beans. Asked if they knew the whereabouts of D. Battery, they could give us no information. In this predicament, lost among a welter of shell craters and gloom, with the German guns 'searching and sweeping' and the horses going wild, the sergeant decided to unload the shells and dump them in the mud. To have taken back the ammunition we would have had to admit the failure of our mission.

It was from this sector that I was given – after seventeen months in France – a two-weeks leave in England. The first week I spent with my parents in Hackney, but for the rest of my stay I took a room at the Eiffel Tower. Stulik was absent from the hotel, having been interned (because of his Austrian nationality) at the Alexandra Palace. My arrival had been noticed by Nina Hamnett, and the news was quickly passed on to several of the diners in the restaurant. Unaware of this, I was upstairs taking a bath, when the door was slowly opened and an officer wearing the green tabs of the Intelligence Service looked in. Beneath the camouflage I recognized Hope-Johnstone, who I learned later was back on leave from Athens. He suggested I should join him in the restaurant below as soon as I was dressed. The electric lighting in the restaurant was somewhat dazzling after many months of candlelit dug-outs. The small dining room was full of animated customers, most of them in military uniforms of various kinds. Hope was seated with a friend, Captain Gerald Brenan, and Augustus John, now an Official Artist with the rank of major. At another table I noticed Nancy Cunard in the company of two Air Force lieutenants. From the other side of the restaurant, but hidden from view by a very large brass bowl filled with ferns and aspidistras that occupied the centre of the floor, someone whom I took to be a discerning amateur was asserting in a loud voice the superiority of the modern French artists over the English. Viola Tree and her sister Iris, who had just arrived, paused to exchange greetings with the actor Sir Gerald Du Maurier and his wife. Above the buzz of the customers' conversation, Madame Stulik, at her position of control behind the small marble-topped service counter, could be heard shouting the orders she had received from Joe the waiter, down the kitchen shaft to the chefs below, who promptly echoed them back again up the shaft to Madame. This sing-song repetition of the orders was to ensure that the chefs had correctly understood what was required of them. These vocal exchanges of orders were continued throughout the entire evening, after this fashion: 'Deux Tournedos avec pommes sauté et épinards à même temps', then again a call for, 'Deux escalopes de veaux avec pommes nature et épinards'. And as the gourmets made their choice from the menus Joe and Madame directed their requests down to the kitchen.

It was a novel experience this first evening at the Eiffel, having for a year or more taken orders from sergeant-majors, sergeants, corporals, bombardiers, not forgetting gunners, to find myself associating with majors, captains, lieutenants, actors, and art critics. With Stulik away, it must have been difficult to run the restaurant with Joe alone to do the waiting, and this was not the only job he had to do. One night I remember seeing him assist two inebriated Australians up the stairs to their rooms while Madame directed the operation from below.

In the First World War London was a great place to spend one's leave. At night in the black-out the streets of Soho were filled with groups of roving soldiers in search of a good time, there being at that date no striptease to divert them from the chase. Slouch-hatted 'Aussies', beturbaned Indians, kilted South Africans, Canadians, and cockneys, crowded the pubs and cafés. In these conditions the Eiffel had to be wary of its visitors. As a precaution against unknown night intruders, a small hole at eye level had been bored in the hotel door and covered with a metal disc. This cover could be moved aside, allowing inspection of anyone outside; if the scrutiny was unfavourable the door remained closed.

As a change from the Eiffel's cuisine, I dined one night in the company of Augustus John, Brenan, and Hope-Johnstone at Paganis in Great Portland Street, where John, perhaps because he was the Official War Artist of the party, amused himself by drawing on his serviette between courses. If this had happened at the Eiffel I feel sure Stulik would have framed the serviette.

The day for my return to the front came all too soon, and I was slow in starting off. But Brenan provided me with a note for my commanding officer in which he stated that I was his cousin and that he was responsible for my delayed departure.

With 'Blighty' left behind, I found myself on the night boat packed with men also returning from leave and once more heading for France.

On a large stretch of vacant ground on the outskirts of Etaples were assembled a mass of troops just back from England. Several electric lamps on tall poles shed a flicker of light which only served to stress the pervading gloom. Sergeants perched on lorries above the crowd were directing the troops to their various units. They called for men of the 51st Division, the 12th and 18th Divisions without artillery. After a number of other divisions had been named, the cry came for men of the 9th Division with artillery, and that included me. The 51st Brigade were occupying a coastal position in the vicinity of Neuport, and D. Battery was entrenched among the sand dunes, with, close by on its left, a stretch of beach and sea beyond, once the delight of sunbathers and holidaymakers, but now deserted and covered with barbed wire entanglements.

On first approach there was an air of peace about the position with the calm empty sea a few yards away. There was too a feeling of isolation, the adjoining batteries being hidden among the hillocks of the dunes. The former occupants had built shelters of solid timber well sandbagged overall. There was also (what comfort!) a dugout furnished with a table, its top covered with zinc and on each side of it two long stools. The place made a useful dining room. From time to time English warships approached the coast and shelled the German positions. This done they withdrew into the sea mist. In retaliation, it seemed, the 'Bosch' would then bombard us. Their shells hitting the hard sand sent splinters flying in all directions, the full force of the blast being on the surface, whereas on softer ground much of the explosion was absorbed. The Germans appeared to have our range, scoring some direct hits on the battery. One midday as several of the gunners were sitting outside the dining-room shelter having a lunch of bully-beef stew, a 'Bosch' shell burst among them, killing two. The dead were placed on the dining table and wrapped in blankets as their blood slowly oozed over the zinc table.

'Fritz's' artillery was especially active at night, firing with a method known as 'searching and sweeping', aiming first in a direct line, then so many degrees left and right, seeking to cut our supply routes, as it was under cover of darkness that our ammunition and food reached us. It was on one of these nights, as we were unloading supplies and the German guns were busy, that we sustained another direct hit. There were several casualties, and I was detailed to be one of a four-man stretcher-bearer party to carry a wounded driver to a field-dressing station about half a mile away. We struggled and stumbled in the dark over the broken ground, striving to avoid the shell holes and barbed wire, doing our best to hold the stretcher level and cursing every obstacle in our path. If one of us tripped causing the stretcher to tilt there was an outburst of foul language from the others. We reached, at last, the dugout that served as a dressing station. Pushing aside the ground sheet that covered the entrance, we staggered inside, placed our burden on the ground, and waited. An orderly who had been attending to some other wounded came to us and lifted the blanket from the driver's face, let it fall again, remarking as he turned away: 'This man is dead.' There was resentment in his voice as if he considered we had played him a trick bringing a corpse to the dressing station. Apprehensive of being caught by a stray shell, we lost no time in getting back to the battery.

In the early part of 1918, we left the coast position, and moving no faster than our horses could walk, with occasional halts for rest in some village on the way, we made for the Somme country. It was about this time that I received a letter from my friend Captain Guy Baker in London. He wrote: 'Lewis is back here on leave, and has been made an Official War Artist. Do some drawings at once and send them to Konody, he is choosing artists to do war paintings for the Canadian War Records Office.' Situated as I was at the time, it was extremely difficult to find the opportunity or the materials to make a drawing of any kind. Fortunately the battery was resting for a few days, and I was able to slip away at odd times to a small unoccupied army hut that formed part of the camp. There, on a sheet of newspaper, I made a drawing whose subject I cannot recall at this date. However, my movements had been observed by a Lieutenant who had recently joined the battery. He was of middle-age, corpulent, and had a purple complexion. It was said that in his youth he had been a professional footballer, and kept goal for some North of England team. He caught me one day in my studio hut as I was finishing my design. In a blustering manner he ordered me to get back at once to my subsection. Later I folded the drawing into an envelope and sent it to Konody.

Under the stress of the war this incident was soon forgotten. Besides, the likelihood of my ever becoming a War Artist seemed very remote until one day, several weeks later, I received the following letter.

Canadian War Records Office,

14 Clifford St, Bond Street, London W1

28th December 1917

To Gunr W. Roberts 123744

D. Battery 51st Brigade RFA BEF France.

With reference to your communication re your being transferred to the Canadians for the purpose of painting a Battle Picture for the Canadian War Memorial Fund. I would be glad to know whether, providing you are given the necessary facilities and leave, you are prepared to paint the picture at your own risk, to be submitted for the approval of the committee. The reason for this request is that the Art Adviser informs us that he is not acquainted with your realistic work and Cubist work is inadmissible for the purpose. If the picture, which would be 12ft wide, is accepted you would be paid from £250 to £300, in case of refusal you would be refunded for material and trouble.

J. Harold Watkins

Captain

For Officer I/c Canadian War Record.

JHW/AM.

After the receipt of this letter there was for several months complete silence on the War Artist front.

Continuing our journey the 51st Brigade moved to a sector of the line covering the town of Albert. Many of the men had been in this part before during the fighting of the summer of 1916. They talked of the heavy fighting around High Wood and Delville Wood and of their dead or wounded comrades. But they also remembered other things, such as the plentiful issue of tins of bully beef, so many, they had been able to make shelters with them. But now, in this beginning of 1918, it was quiet in the Somme country. D. Battery was encamped behind the line near the village of Etinehem. In this place a photographer was doing a brisk trade among our men who were lining up to have their photos taken. I too joined the queue. A special treat was the issue of a number of day passes to visit Amiens.

The town seemed deserted, and the cafés and shops closed. I wondered what we could find to do here. As we wandered through the empty streets the silence was broken only by the clatter of our heavy army boots on the paving stones. My companions had but one purpose; to find a brothel, or as the 'Tommies' would say, a 'red light'. But as I lacked the courage to take part in that sort of combat we parted company. A passing tram with a few passengers showed that there were still some inhabitants left in Amiens. I ended my visit by a tram ride through the town.

Although as far as I know gas was not used in the Somme, this incident concerns gas. On a dark foggy afternoon three men were sent to the wagon lines a couple of miles away to collect the battery rations. Night came on and they had not returned. A proposal to send out a search party was contemplated, when someone discovered them in the battery latrines, collapsed on the ground muttering and laughing hysterically. At first it was thought they were suffering from the effects of laughing gas until two large empty rum jars were found close by. They had drunk the battery's entire rum ration. There was no issue of rum that night, not even for the sergeants.

Apart from the commanding officer, the next important man in the battery was the one who cooked our food. D. battery's cook was a tall man whose face and uniform were almost black from the constant use of creosote with which he lit his fires. His never-ending supply of fuel came from the empty ammunition boxes that had contained the shells that were used to put 'Fritz's' fires out. Our cook's first job of the day was to make six large 'dixies' of tea of a good strong brew – a dixie resembles an outsize oval pail. The breakfast bacon was then fried in the dixie lids. The fat from the frying – known as 'gipo' – was much sought after by the men. Something like a rugby scrum took place around the lids placed on the ground, each one trying to dip his bread in the delicious liquid, some getting more mud than gipo on their bread. The dixies came into use again at lunch-time with bully-beef stew, and once more with tea to end the day.

The cook, besides preparing our meals, also ran a crown and anchor board, sold Abdulla cigarettes, biscuits, and bars of chocolate. On one occasion, when the battery was at rest behind the line, he was able to use a tent as a canteen. I shall always remember that tent, for one afternoon after making a purchase, I inadvertently left my paybook there. Although I returned immediately, it had disappeared. The cook hadn't seen it, nor had any of his customers. It was a piece of bad luck since it contained £50 in notes sent to me by Ezra Pound who had sold two of my paintings to the American collector John Quinn.

In our new position on the Somme, we formed part of General Gough's 5th Army. Although on arrival things seemed quiet enough, by the time the battery went into action the situation was less peaceful. As the Guards who held this sector of the line were being relieved, the Germans made a sudden attack, capturing a certain amount of territory. The Guards, who had been brought back into the line, counter-attacked and reoccupied most of the ground 'Fritz' had taken. There seemed now to be a pause in the fighting as our battery moved into position, no shell bursts, no machine-gun fire, no rifle shots. When the Germans had been forced to fall back, they had abandoned some of their field guns which now stood isolated in no-man's land. The commanders of the 51st Brigade batteries arranged among themselves to try and salvage these guns. D. Battery's task – and it was rumoured that our major had chosen the hardest – was to bring in two field howitzers that had been left a short distance beyond our front lines. On the night fixed for the undertaking, our salvage party having been given a double tot of rum, then set off with two six-horse teams, to do the job. The horses were left behind our own line while we crept out. Fortunately there was no barbed wire to tangle with and we endeavoured to free the gun wheels embedded in the hard earth. Without arousing any hostile activity from the opposite trenches, we manhandled the two howitzers to where we had left the horses.

There was a strange silence round about during this operation with not even a star-shell to disturb the friendly cover of darkness, due to the fact perhaps that this part of the line, having recently been the scene of attack and counter-attack, had become disorganized. This calm contrasted strongly with the feeling of restlessness and apprehension experienced in the forward areas of a stabilized front at night. The burst, from time to time, of a star-shell spreading its pale white light over the trenches and no-man's-land, then the anxious watch for enemy activity before the light slowly fades out into darkness once more. Again, the nerve-jarring rattle of machine guns, together with the thud, thud of trench mortars, or the sudden burst high in the night sky of three red Very lights, the SOS from our infantry calling for artillery action against a German raid on their trenches, and the uproar of the bombardment that followed. The batteries were prepared for night firing, the guns being sighted upon an upright stick or aiming point, called a night-line planted a few yards in front of each gun, they were in this way set ready upon their target: the 'Bosch' trenches. When these two war trophies had been brought to our wagon lines, I was asked by the commanding officer to paint on the shield of each gun an inscription stating that they had been captured by D. Battery, 51st Brigade, 9th Division.

Shortly after this unexpected request, I was told to accompany an officer to an observation post in the front line and make a drawing of the terrain beyond. From the OP I saw a completely featureless landscape, save here and there a few broken sticks of trees. I made a pencil drawing of this barren piece of ground, but what use my superiors would be able to make of this sketch I could not imagine. There was one interesting moment during this visit to the OP. Through his field glasses the lieutenant spotted what appeared to be a German working party constructing shelters with cupolas. He handed me his glasses while he phoned back to the battery giving the position of the target and requesting three rounds of gun fire. With the first shell bursts the gang dived out of sight. There was something comic in the way those tiny figures suddenly dispersed. Our action brought no return fire from the 'Bosch' artillery; on his side all was still quiet. Reflecting at a later date upon these two unusual tasks I had been asked to do, the explanation perhaps was that instructions for my return to England had already reached brigade headquarters, and that they were giving me some tests of their own. However, the Germans did not leave us long to exult in the possession of their two howitzers, and very soon we had more pressing matters to think about than captured trophies.

The calm that had long prevailed on our front ended suddenly one night with a heavy bombardment of our battery position and wagon-lines by the German artillery. Several shell bursts near the corrugated iron stables in which the horses were housed caused a panic among the animals inside. Meanwhile, the men in the darkness, lit only by bits of candle placed on the floor, struggled to get them unchained. In spite of the darkness and confusion, I managed to extricate one horse from its prancing and snorting stablemates and led it away from the bombarded area to a field a half-mile distant that had been made a point of rendezvous to which the wagon teams and men were being evacuated. This chaotic night was the beginning of the battery's long retreat, staying only long enough at our various halts to fire a round or two, sometimes not even that long. At a village where we had stopped to rest, at about the hour of midnight, with everyone lying around asleep and me by the telephone too restless to sleep, came a sudden call from brigade with the order to move on at once. Had I not been awake at that moment to arouse the battery, most likely 'Fritz' would have done it later.

This telephone matter reminds me of another phone incident that happened to me in a village at Arras. I was on telephone duty one morning with the instrument on the table before me. In order to be ready for morning parade I took off my tunic and began to polish the buttons. At that moment the door opened suddenly and the orderly officer with the sergeant-major stood in the doorway. The officer with a severe manner said: 'Why aren't you wearing the earphones?' This was the reason I later found myself on a working party digging gun-pits before the start of the Battle of Arras. I fancy that besides being a working party, we were also a party of delinquents. Nevertheless, I feel my Somme exploit atones for the Arras affair.

On another occasion during our Somme retreat the battery took up position facing an embankment. It seemed that we would at last make a stand, and were already planning our dug-outs, when, following two days of inaction, we took to the road again with all speed as 'Fritz's' machine-guns bullets whistled over our heads. Staggering along, trying to keep up with the gun team, I was stopped by Lieutenant Duthey mounted on his horse. He had recently returned from leave, and had brought back from England two small puppies. In the battery's speedy evacuation of its position, he had forgotten his pets. As he galloped by he called to me to go back and get them. I rescued the pups but hardly enjoyed doing so under fire.

At one halt on our line of retreat, we were visited by two red-tabbed gold-braided staff officers known to the troops as 'Brass Hats' or 'Top Brass'. They inspected the lay of the land where we had stopped, and it was decided that the battery would go into action on a rise in the ground in the vicinity of the road. This settled, the 'Brass Hats' departed. That night we began firing, but almost at once 'Jerry's' field guns replied with direct hits on our position. The battery was not dug in, and as I crouched low by the trail of our howitzer I could see between the wheels sparks from the German shell blasts on the ground a few yards ahead. A pious member of our crew exhorted us to turn our thoughts to God. The position had been badly chosen, and it was said that the enemy could see the flash of our guns when we fired. However, we did not stay long enough to put this theory further to the test.

As the battery continued to move away from our original Somme position, there were signs that our sector had become disorganized. Even the German prisoners seemed to know it, for in passing a field containing a large crowd of them, some wounded, several called to us and waved their arms with a gesture which meant that their compatriots were advancing.

A large marquee field hospital standing empty appeared to have been evacuated in haste to judge by the confusion of camp beds, stretchers, blood-stained wads of cotton-wool and bandages, together with bowls partly filled with the blood of wounded men. A mile or so past the marquee, we encountered a party of infantry also on the retreat. They were in high spirits, had got rid of their rifles, and were dancing and gesticulating and at the same time shouting 'The War is over!' A car conveying some staff officers that was passing, stopped suddenly, two of the officers got out and tried to persuade the 'Tommies' to come to some sort of order and discipline. What success the 'Brass Hats' had with these stragglers I cannot say, for our battery moving onward did not stay to find out.

As we approached Amiens on our way to Messines and the Ypres sector, the Australian heavy artillery covering the town was going full blast pounding the German advance to a standstill. The new position we occupied at Messines saw the end of my service with D. Battery 51st Brigade, for shortly after moving in I received instructions to pack my kit and report to the Town Major at Poperinghe. This was the first stage of my journey to England. I reached Poperinghe about midnight. To let me know, perhaps, that I had not entirely got free of them, the Germans were throwing an occasional 5.9 into the town. On reporting to the office of the Military Police, I was shown by a tall 'Red Cap' into a small room, a kind of cellar with straw covering the floor, probably used on occasion to house prisoners. Here I spent the night. The next morning, 10 April, I was off to Hazbrouke the last stop on my journey to Le Havre.

This was a time of crisis, and those who could use a rifle were being sent into the firing line from the base depots; storemen, clerks, even cooks. It seemed strange to be returning to England at this time. As I stood alone on the platform of Hazbrouke station awaiting my train, I saw on the opposite platform among the crowd of troops preparing to leave for the fighting zone my Vimy Ridge antagonist Gunner Kelly. He seemed flabbergasted to see me travelling in the opposite direction to himself and the rest of the troops and shouted to me something I couldn't understand. I imagine it was 'Jesus Christ man why aren't you over on this side with us?'

The ten days spent at Le Havre base depot were employed in camp fatigues. By way of a change we did gas-mask drill. Wearing our gas-masks, we had to pass through a narrow covered trench or dug-out blanketed at both ends and filled with poison gas. These practice sessions helped to pass the time. On the morning of 20 April I arrived at Victoria. I was the only passenger to get off the train in a deserted station, except for one woman waiting by the barrier. She asked me if I had met her husband in France, a Private 'so and so' I forget the name, but I was unable to give her any information.

My first visit on reaching London, was to Captain Watkins of the Canadian War Office. Afterwards I made a call on Paul Konody at his flat in the Albany for further information. He showed me a list of the artists who were being employed and the subjects they were to paint. He said that all except one had been allocated and that concerned the first gas attack upon the Canadians at Ypres. Although I was without experience of that kind of cloud gas warfare, and told Konody so, I accepted the commission. Next and last of my interviews was with Robert Ross, one time friend of Oscar Wilde. This took place at his flat in Dover Street. A small rotund, sallow complexioned man greeted me. Our meeting was brief. He asked what medium would I use to paint my picture, I replied: 'Oil.' Nevinson, he said, for his, was going to use marble medium. I remarked that this was a method new to me. After a pause, he glanced at me doubtfully and said; 'You are William Roberts aren't you?' I assured him I was, and at this the interview ended. I never quite understood what part Ross had in the Canadian War Paintings scheme. He died soon after our meeting.

Shortly after my return to London, I participated in a small luncheon party at the Eiffel Tower. Those present besides myself were Colonel Ford-Hueffer of the Welch Regiment and friend Violet Hunt, Lieutenant Wyndham Lewis of the Garrison Artillery, and friend Iris Barry, and Captain Guy Baker, who had served in the Boer War and was at present home from France on sick leave. After a while the conversation turned upon War Artists. Hueffer said that Duncan Grant should be made a War Artist and invited to paint a war subject. Hesitantly I remarked that Grant would hardly wish to do a picture dealing with the war as he was a conscientious objector. The colonel turned to me and snapped sharply: 'Well, what does that matter?' Intimidated by his rank and manner, I remained silent, inwardly thankful that I had joined the Artillery and not the Welch Regiment as Lewis had advised me to do.

To paint the 'Gas Attack' I was 'Transferred', 'Loaned' perhaps would be a better word, to the Canadians for six months. I continued to wear my Royal Field Artillery uniform, but lived free from military duties, as a civilian, and at my own expense. I took a studio in Flood Street, Chelsea (rent paid by the Canadians) and spent the summer of 1918 working there on my 12 by 10 foot canvas. Later in the year, the collection of Canadian War Paintings was exhibited at the Royal Academy. When I had finished with the Canadians, I did not return to France because the British Ministry of Information, who had their own War Records organization, commissioned me to do for them a painting of a 'Shell Dump'. For this I was paid by monthly instalments, but before this picture was finished the war was ended.

One day, while still at work on the 'Shell Dump' I met near my studio a ginger-haired young man who had been a driver in my subsection of D. Battery. He said he had finished with horses and was now on an instruction course in motor engineering that was being sponsored by the Government. Before we parted, he related an incident concerning D. Battery's Commander Major Morrison. During the final phase of the war in France, the major was wounded and lost a foot. As he was being carried away on a stretcher, he sent a man back to get his foot saying he was not going to leave it behind for the 'Bosch'. Knowing the major I am prepared to believe the story.

It was about this time, whilst still in uniform, that I had a final 'contretemps' with the Army. Passing one summer evening by Wellington Barracks, as the Guards were marching back and forth across the parade ground, with rifles at the slope and bayonets fixed, I stopped among the sightseers to admire the troops as they moved in step to the martial music of their band. Absorbed perhaps in the memory of a similar parade on Horse Guards one spring morning some two years before, I had not noticed that the marching had stopped and the music had changed to the National Anthem until I felt a sharp tap on my shoulder from behind and heard a voice say 'Jesus Christ man stand to Attention.' Turning I saw the scowling face of a 6-foot sergeant of the Irish Guards. It was not Kelly this time, but one of his equally aggressive compatriots.

With the war ended and no more war paintings to be done, it was now time to give up my uniform and regimental number. So on 15 October 1919 at the Royal Field Artillery Depot, Woolwich, I was demobilized and transferred to the Army Reserve.

In remembrance of Major Morrison, Captain Delahaye, Captain Logan, Lieutenant Duthey, Sergeant-Major (Spud) Murphy, Corporal Garrity, Gunners Tom Gunn, Cockney Sharpe, and Kelly, Drivers Thorpe, and Nobby Clarke. Together with the other members of D. Battery whose names were either unknown to me or have been forgotten.

The front cover of 4.5 Howitzer Gunner / Memories of the War to End War 1914–18

News | Gallery | Auction results | The artist’s house | Contact

List of works illustrated on the site

Catalogue raisonné:

chronological | alphabetical