AN ENGLISH CUBIST

DAVID CLEALL:

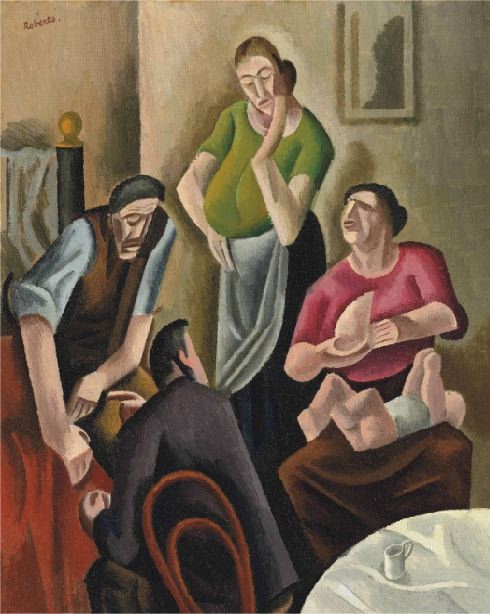

William Roberts, The Poor Family

Illustration © The Estate of John David Roberts. Text David Cleall, from Christie's London, Modern British and Irish Art, 12 December 2012 (lot 35).

The Poor Family (aka Unemployed), 1921–3

Oil on canvas, 50.8 cm x 41 cm

Poverty was a subject that Roberts knew at first hand. After the First World War he began living with Sarah Kramer (sister of the artist Jacob Kramer), who soon became pregnant. Their son, John, was born in 1919. Roberts was selling little – he wrote to his former teacher Henry Tonks that 'I have had such a struggle to make a living at all that I am at times almost driven to despair' [1] – and through personal experience he would have been very familiar with the type of claustrophobic interior space of The Poor Family. The cramped room serves as a sitting room, a bedroom and a bathroom for the family. For Sarah and William Roberts their rented room had also to serve as an artist's studio. However, this painting does not seem to be autobiographical. Whereas Sarah Kramer and William Roberts lived an impoverished 'bohemian' lifestyle in Fitzrovia – 'love among the artists' as Sarah used to characterise it [2] – the 'poor family' shown in the picture are robustly portrayed as working class, drawing upon social types familiar to Roberts, the son of a Hackney carpenter.

Roberts's immediate post-First World War work is now best known through his large-scale compositions showing everyday life for working-class Londoners. His milieu is the street corner, the pawnbroker's, the park, the music hall, the cinema and the bus stop. In contrast to these highly populated works, The Poor Family is powerful through being a tightly focused composition – a couple with a baby in the foreground and presumably parents or in-laws in the background. By placing the viewer in an intimate relationship to the subjects, Roberts emphasises the psychology of the interpersonal relations depicted – a feature developed in two of his later interior compositions, The Restaurant and The Chess Players (both c.1929). The interplay of looks between the mother, preparing to feed her baby, and the father has immediacy through the way Roberts's captures mid-motion the turn of the father's head. The title 'The Poor Family ' prompts the viewer to read the scene as one of concern for the future of a child born into a situation of dire poverty – a situation that is probably all too familiar for the older couple. The simplified features of the weary faces with their downcast eyes seem to exemplify resignation and hopelessness.

When, in 1964, Roberts reproduced The Poor Family in his self-published William Roberts A.R.A. Paintings and Drawings 1909–1964 (p. 14) he gave the painting the title Unemployed. This gives the picture a more political point which may have been considered unpalatable to potential buyers when the work was first exhibited, in 1923. With the title Unemployed, the topic of conversation for the group is suggested, and the younger man's pointing right hand seems to indicate the powerful arm and hand of the elder man, perhaps evoking the common figure of speech of 'hand' standing for 'hired man', or in this case someone waiting for hire. At the time Roberts worked on this painting, around 1922, unemployment in Britain had reached a post-war high of 2.5 million. In the East End of London, thirty councillors of Poplar had been arrested and imprisoned for their actions to alleviate local poverty as a result of unemployment, and there had been mass demonstrations in their support. Although Roberts rarely expressed explicit political views, just before the war he had lived in an artists' commune set up by the eccentric socialist Stewart Gray, who had led a number of hunger marches and demonstrations to highlight the problem of unemployment.

The Poor Family was painted at an important time for William Roberts as he emerged from the temporary security of his official war-artist commissions and prepared for his first one-man exhibition, in 1923. His brief as a war artist had encouraged 'realistic' rather than 'Cubist' work, and Roberts produced an extraordinarily powerful group of watercolour drawings on war subjects that may best described as 'expressionistic' in their spontaneity of line, intensity of mark-making, use of livid colour, and selective distortion of the human figure. In looking for post-war subjects, Roberts turned to the drama of everyday life and inflected often downbeat subjects with a modernism that in some cases is expressionistic – in the manner of his war pictures – and at others exhibits an excitement about form, design and geometric shape that has its roots in Roberts's Vorticism and looks forward to his very idiosyncratic mature style.

It is expressionism that is to the fore in The Poor Family, with viewers being immediately drawn into the pathos of the situation through the family's sculptural, almost mask-like, faces. Roberts had seen tribal masks in collections by Jacob Kramer and early patrons Sacheverell and Osbert Sitwell, and was very familiar with the influence of 'primitive' art on Picasso, Derain and Modigliani – all of whom had exhibited at the Mansard Gallery, London, in 1919 in an exhibition for which Roberts had designed the poster. In The Poor Family, the face of the centrally standing woman – privileged in the picture's composition – is rendered through simple lines in the manner of a Modigliani portrait, though Roberts resists creating individual portraits and chooses instead generalisations that evoke broader responses in the viewers. The similarities and differences with Newspapers (1926) are instructive. In this later work, Roberts once again groups four figures around a table in a bare interior. However, the expressionism has now been largely played down, and 'cubist' elements such as the angles of the newspapers and the still life on the table seen from a heightened perspective are now more dominant.

[1] Photocopy in the Tate archive (William Roberts Box 3) of an undated letter sent from 32 Percy Street, London W1, and hence datable to 1918–19 (original believed to be in the Harry Ransome Center, University of Texas at Austin). In (probably) early 1925 Roberts wrote to William McCance that 'the financial position is such that I feel proud when I am able to produce the cash for the next days [sic ] meals' (ibid.)

[2] Pauline Paucker, Sarah: An Anecdotal Memoir of Sarah Roberts, Wife, Model, Muse and Defender of William Roberts RA (Tenby: William Roberts Society, 2012), p. 10.

Home page | Chronology | Bibliography | Collections | Exhibitions

News | Gallery | Auction results | The artist’s house | Contact

List of works illustrated on the site

Catalogue raisonné:

chronological | alphabetical