AN ENGLISH CUBIST

DAVID CLEALL:

The 1965 Roberts retrospective

Illustration © The Estate of John David Roberts. Text © David Cleall, from the April 2015 William Roberts Society Newsletter

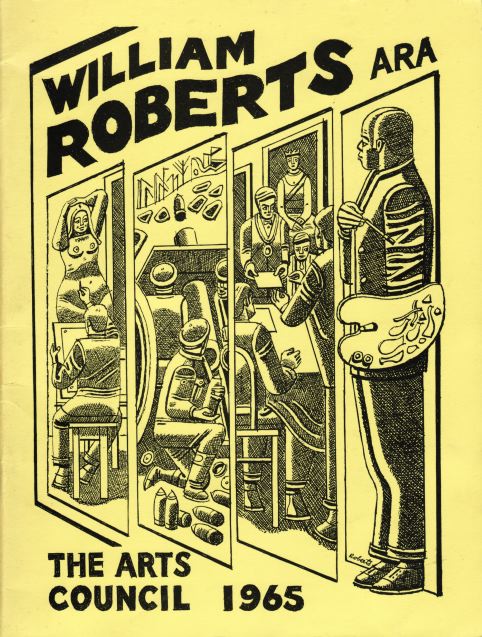

William Roberts ARA, 1965

Pen and ink, 24 cm x 18 cm

In the winter of 1965, the Tate Gallery and the Arts Council staged a major William Roberts retrospective exhibition. Norman Reid had recently succeeded Sir John Rothenstein as director of the Tate, and in an early staff reorganisation Ronald Alley became keeper of the modern collection. Alley had been with the Tate for a number of years, and this promotion enabled him to more effectively continue his work in revitalising the modern collection.

William Roberts was now 70. In 1961 he had been given an award by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation 'in recognition of his artistic achievement and his outstanding service to British painting', and his earlier election as an Associate of the Royal Academy had led to various duties on the RA council. However, he was known mainly through the large-scale works exhibited each year at the RA Summer Exhibition, and the extraordinary range of his work had not been recognised. Now a major retrospective was planned, and Ronald Alley would curate it.

Alley had championed Roberts in his role as purchase adviser to the Cecil Higgins Art Gallery in the late 1950s, and it is likely that a number of recent Tate Gallery Roberts acquisitions – The Diners, Athletes Exercising in a Gymnasium and The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel – were also the result of Alley's support. Roberts couldn't have been served by a better curator than Alley, who was passionately enthusiastic about modern art and had close friendships with many internationally recognised artists, including Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Francis Bacon. He also had a reputation for the thoroughness and accuracy of his research – completing a catalogue raisonné of Bacon's work in 1964. Most important to an effective working relationship with the Robertses was Alley's unpretentious and self-effacing manner.

Alley set to work tracking down the key pieces in Roberts's output. The two major private collections of the artist's work cooperated with Alley – Ernest Cooper lent 15 oil paintings and 18 drawings, while Honor Frost, the executor of the late Wilfrid Evill (who had died in 1963), lent 7 oil paintings and 7 drawings. Other private collectors lent a further 45 pictures, including such rarely seen and important works as Dock Gates, The Garden of Eden, Christ Driving the Money Changers from the Temple and Susanna and the Elders, and 68 works came from national collections (including the Tate). Most excitingly of all, Alley brought the huge Canadian War Memorials commission The First German Gas Attack at Ypres across from Canada, The Chess Players from New Jersey, and Interval Before Round Ten from Australia. The Robertses lent 33 works, including a 1909 Study of the Artist's Father, Brother and Sister, portraits of Sarah, and self-portraits including the recent self-mocking Self-portrait With Knotted Handkerchief (1964) – an indication that Roberts didn't want to be seen as taking himself too seriously. A grand total of 222 items (212 plus 10 life studies) were exhibited at the Tate Gallery, with a slightly smaller exhibition moving on to the Laing Gallery in Newcastle in January 1966 and finally to the Whitworth in Manchester.

Ronald Alley contributed a concise introductory essay to a detailed, well-illustrated catalogue. Roberts's cover illustration – a pen-and-ink drawing printed on lemon-yellow card (above) – showed him looking back over three phases in his life: first the Slade, then his war experiences, and finally Roberts the ARA.

It is difficult to imagine that Roberts would not have been very satisfied with the show, although we have no record of his response other than that he was pleased by the space allocated and the resulting uncramped hang. Nor is the public response documented – though Edward Burra went in November and declared himself 'fascinated by the William Roberts exhibition at the Tate'.

The art critics varied in their responses, though many of them provided detailed and thoughtful analyses of Roberts's work and some were very welcoming of an opportunity to re-evaluate the artist.

Andrew Forge in the New Statesman (26 November 1965) declared that 'The William Roberts exhibition which Ronald Alley has arranged for the Arts Council at the Tate is a real event. It confirms that Roberts is one of the most unfairly neglected artists of our time. It also shows him to be a more complex and disturbing artist than we had ever imagined.'

David Thompson in The Spectator (26 November 1965) wrote:

It's a highly stylised art, but exceedingly lively, and as it's done with unflattering precision both on a very large and a very small scale, it adds up to something pretty impressive . . . He has a marvellous eye for telling and curious detail, a keen observer's interest in gesture and expression . . . This is one of those overdue and eminently worthwhile retrospectives that make one ashamed one didn't know more about an artist before . . . [T]his exhibition makes nonsense of Lewis's claim to have been the be-all and end-all of Vorticism.

T. G. Rosenthal in The Listener (2 December 1965) noted that

above all, Roberts has a remarkable organizational ability in that he can crowd a canvas or a drawing, such as Camel March of 1923 . . . with a multitude of people without ever losing the sense of form or space. William Roberts is no path-finding genius, but he is very much an artist to be respected and an essential chapter in the history of twentieth-century English painting,The Times (20 November 1965) struck a more negative note: 'currents of opinion in England have alternated between welcoming his work and forgetting it entirely . . . Mr. Roberts is really a modernist in style but not in spirit.' However, the critic singled out the smaller, earlier pictures for praise – works such as Rustic Scene – and commented '[In] the earlier, adventurously coloured bicycle picture "Les Routiers" he has captured vitality in the forms themselves, not merely reflected in the faces.'

Frederick Laws in The Guardian (24 November 1965) noted, 'He is one of the few English artists to have seen the possibilities of Cubism early and to have sought to domesticate it . . . He has persisted in the service of an individual vision without fashionable approval or popular success'. Again the early work was favoured, as being 'of great power and inventiveness'.

Frank Whitford in the Arts Review (11 December 1965) discused at length what he saw as the shortcomings of an artist who had hardly allowed his work to change over the years; however, he concluded by noting that 'paradoxically these paintings which are so stylised, often forced and mannered in the extreme, are nevertheless frequently memorable and extremely stimulating and exciting. How is it that paintings with such obvious and glaring faults deeply affect the imagination?' Whitford answered this question with reference to The Gutter, where 'each gesture, each inflection of the hand and tilt of the body fits in with its neighbour like a piece of turned polished steel fits into a machine. It is the completeness and utter lucidity of Roberts' formal sense which give his work its convincing claim on our attention.'

Terence Mullaly in the Daily Telegraph (6 December 1965) enthusiastically commented that 'Thanks to the Arts Council it can now be asserted that in our own time only Stanley Spencer deserves as high a place in this company ["that very English tradition of highly individual and eccentric painters"] as William Roberts.' Mullaly particularly praised the 'savage, yet restrained power' of the First World War paintings, but also added that 'What is now clear is that there is a gentle and more reflective side to his work. [That] is to be seen in his portraits.'

Keith Roberts the Burlington Magazine (January 1966) stood alone in launching quite a personal attack on Roberts: 'The whole affair has been organized and catalogued by Ronald Alley with a zeal and scholarly precision worthy of a better artist. For when all is said and done . . . Roberts is a minor figure.' As the review continues it seems that Roberts's satirical depiction of the Bloomsbury set has particularly rattled the reviewer:

That a supposedly modernist avant-garde artist should attack kindred spirits may seem ironic; that is until one begins to appreciate how superficial Roberts's own 'modernism' really is. His jibes at the Bloomsbury Group are not only tiresome but unjustified since his own position is actually close to that of Bell and Grant. His art represents a characteristically English dilution, along narrative lines, of an essentially formal concept stemming from Europe.

In other circumstances this might have led to a Roberts pamphlet, but in the context of what appears to have been a very successful exhibition Roberts seems to have let this pass, and within a few months he must have felt vindicated by being elected a full Academician at the RA.

Home page | Chronology | Bibliography | Collections | Exhibitions

News | Gallery | Auction results | The artist’s house | Contact

List of works illustrated on the site

Catalogue raisonné:

chronological | alphabetical