AN ENGLISH CUBIST

DAVID CLEALL:

William Roberts, Masked Revels

Copyrighted material on this page is included as 'fair use', for the purpose of study, review or critical analysis only, and will be removed at the request of the copyright owner. Text © David Cleall, from Christie's London, 20th Century British and Irish Art, 23 May 2012 (lot 15).

Masked Revels, 1953

Oil on canvas, 112.1 cm x 90.8 cm

Masked Revels was painted in 1953 in what can now be seen as a brief period of stability and optimism for William Roberts and his wife, Sarah. In 1946 they had moved into an unfurnished single room in a letting-house in St Mark's Crescent, Primrose Hill, and now, seven years later, through good fortune and the generosity of a friend of Sarah's, they found themselves the owners and sole residents of this fine property on the Regent's Canal. For the first time in thirty years of married life Roberts had a secure home, with room enough for a studio. He had also acquired a new patron, Ernest Cooper, the successful owner of three health-food shops in central London. Cooper was to become Roberts's chief patron, eventually acquiring some 20 oils and nearly 50 other works. Masked Revels, along with its watercolour study, was purchased by him directly from the artist.

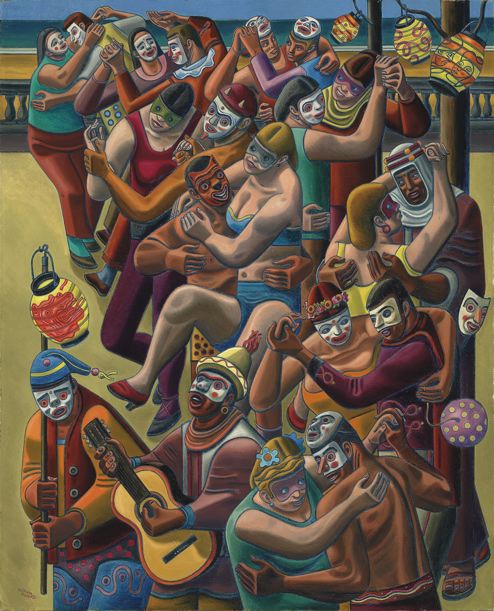

Masked Revels is an excellent example of Roberts's complex, highly populated compositions, similar in this respect to the two large-scale works, The Revolt in the Desert and Trafalgar Square, selected for the Royal Academy in 1952 and 1953 respectively. In a succinct catalogue entry for his 1965 Arts Council retrospective, Roberts noted of Masked Revels, 'People in fancy dress'. [1] This typically literal description of content downplays the painting's thematic interest and the intriguing interrelation of characters. Unusually, for Roberts, Masked Revels does not seem to take specific inspiration either from direct observation of life or from a classical or biblical text. However, its depiction of physical desire relates it to other paintings that Roberts produced in the 1950s. The Temptation of St Anthony (1950–51) uses the story of the saint for a startling depiction of a man being taunted by female sexuality, while The Birth of Venus (1954) provides a more humorous take on male inadequacy in the face of female beauty and sexuality. The Rape of the Sabine Women (1955–6) shows a darker aspect of male sexuality and power. Masked Revels is a more celebratory work, showing wild but joyous abandon to music, colour and life. A focal point is provided by a centrally placed 'devil' embracing a voluptuous, scantily clad woman. All six of these eye-catching, large-scale paintings were shown in the Royal Academy's Summer Exhibitions over a period of five years. The Temptation of St Anthony is owned by the Tate, The Revolt in the Desert by Southampton Art Gallery and Trafalgar Square by The Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth.

The masquerade depicted in Masked Revels has a simple, seaside location, and the carnival masks, the guitarist and the tanned, bare-chested male figures suggest a hot Mediterranean evening. The spirit of carnival is evoked in a scene that a few years later might have been described as 'Fellini-esque'. In Roberts's earlier painting The Masks (c.1932), the masks create a mysterious and somewhat frightening view of an unfathomable adult world seen from a child's perspective. In Masked Revels, however, similar masks, in the context of a party, are shown as merely playful aspects of flirtatious behaviour. In both works some of the figures place their masks on the top of their heads, revealing the 'real' selves beneath the assumed identities.

Roberts adopts a typically high viewpoint in relation to the revellers, compressing space and creating an exhilarating juxtaposition of arms, legs, hands and faces that can be seen as a development of his idiosyncratic take on cubism. The dynamic diagonals around which the nine dancing couples and the guitarist are organised are a further Roberts's trope, and in this case the composition is effectively anchored with a lone, sad clown who clings to his Chinese lantern's pole, appearing to make eye contact with the viewer and seeming to plea for a return to reason. This interpretation seems to be supported by a mask on the extreme right of the canvas that appears to raise a quizzical eyebrow in an expression recognisable from many of Roberts's later self-portraits. The tight composition has been carefully planned through a drawing and a watercolour sketch of the same subject. The watercolour was exhibited by Phipps & Company Ltd in 1991.

Even from his early Vorticist work, Roberts had been recognised for a bold and experimental approach to colour. Returning to large-scale oil painting in the 1950s after a period of working predominately in watercolour he employed a particularly playful and highly coloured palette. In his portrayal of T. E. Lawrence and Bedouin leaders in The Revolt in the Desert significant liberties were taken in relation to the colour of otherwise traditional Arab costumes. In Masked Revels, the party costumes provide a perfect rationale for further experimentation with vibrant colours and combinations such as teal and orange, puce and pink, turquoise and purple. In a number of Roberts's pictures over the previous decade the decorative elements on fabric designs had joyously threatened to take over the composition. Bold foliage prints on clothing and furniture in The Flower Arrangement (1944), for example, both complement and compete with the titular floral display. In the recently completed poster design for London Transport Hampstead Fair (1951) a riot of spotted balloons in the bottom right of the composition presented an alternative and attractive abstract pictorial world. Masked Revels further extends this tendency. Spots, stripes, whirls and flower motifs decorate costumes and accessories with delirious effect as befits a carnival.

In 1958 Roberts was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy, and his paintings exhibited at the RA continued to have popular appeal. However, the later 1950s were to be a difficult time for him. Out of favour with the art establishment, Roberts, nonetheless had some champions. John Berger in a collection of essays Permanent Red (first published in 1960) could have been referring to Masked Revels when he noted, 'Roberts is an artist of great sensuous awareness; his colours, his love of physical energy, his women who are too big for their clothes, all demonstrate this.' [2]

[1] William Roberts ARA: Retrospective Exhibition (London: Arts Council, 1965), p. 20 (no. 89)

[2] John Berger, 'Artists Who Struggle: William Roberts', in Permanent Red: Essays in Seeing (London: Methuen, 1960), p. 89.

Home page | Chronology | Bibliography | Collections | Exhibitions

News | Gallery | Auction results | The artist’s house | Contact

List of works illustrated on the site

Catalogue raisonné:

chronological | alphabetical