AN ENGLISH CUBIST

MATTHEW STURGIS:

Roberts and Sickert

Illustration © The Estate of John David Roberts. Text © Matthew Sturgis. This article first appeared in the January 2013 William Roberts Society Newsletter

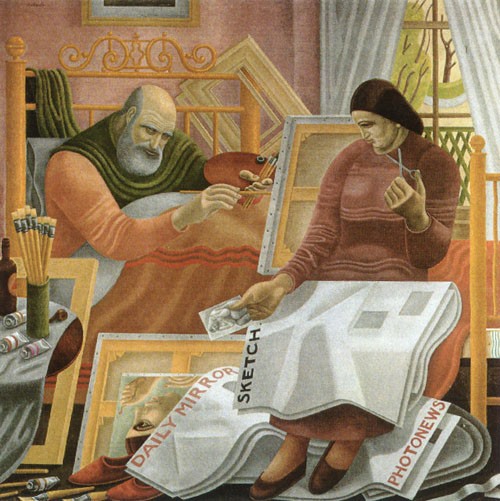

William Roberts, He Knew Degas, 1938

Walter Sickert held a unique position in the British art world during the first decades of the twentieth century. And it was a position that he enjoyed. He was a both a mage and a maverick. He was a forward-looking radical steeped in the traditions of the past. The son of a painter (who had trained in Rome, and in Paris under Thomas Couture), he himself had been a pupil of Alphonse Legros, a disciple of (and studio assistant to) Whistler, a privileged friend of Degas (from whom he had learned much about the techniques of Ingres and Corot and other early French masters). This accumulated knowledge gave him an abiding sense of connection and continuity. He was bound, as he put it, by a 'golden thread' to the line of the old masters – and he felt it was his duty to pass on his knowledge, to extend the tradition, to maintain the golden thread.

When Sickert returned to London in 1905, at the age of 45, after some six years of self-imposed exile in France, he made it his mission to revitalise British painting. He was shocked to find the native tradition so moribund: so limited in its aims, so 'polite' in both its subjects and its treatment – and so expensive that it could be bought only by plutocrats and aristocrats (or, more properly, their culturally ambitious but culturally ignorant wives). For the next 35 years he sought alternative approaches to picture-making and picture selling, and he encouraged others to do the same. He wrote extensively in the press, and he either formed or supported a succession of exhibiting societies: the Fitzroy Street Group, the Camden Town Group, the Allied Artists Association, the London Group. And in almost all these ventures he harked back to the lessons he had learned – via Degas – from the example of the Impressionists.

His personal contacts with William Roberts were slight. They were both members of the London Group. But Sickert, the older man by thiry-five years, recognised in Roberts a true fellow artist, a man with an independent vision and a total dedication to his craft. He lost few opportunities to praise and encourage him. In May 1925, writing in the Morning Post, he described how 'If I make a fortune I shall have a Roberts drawing-room' (to go with a dining-room 'hung with Jack Yeats'). In a letter to the Sunday Times on 20 May 1928 Sickert remarked, 'Pupilage has nothing whatever to do with seniority. I should like to take finishing lessons from Roberts.' Roberts cannot but have been thrilled and impressed by these endorsements.

If he remained grateful to Sickert for his kind words, he seems to have become increasingly bemused by Sickert's own artistic practice. Beginning in the early 1920s Sickert abandoned his use of drawings as the preliminary stage for his paintings, and began to use photographs (either taken by himself or cut out from the newspapers).

For Roberts – as for many artists and critics and members of the public – this seemed a sort of betrayal of artistic integrity. It was cheating! Sickert was unapologetic. He relished black-and-white photographs not because they spared him the trouble of drawing a motif, but because they contained so much tonal information. 'Tone' – the gradations of light and shade – was what most fascinated Sickert as painter.

A press photo provided him with a complete tonal account of any scene. He would then use it as the basis for a tonal underpainting – or camaieu – done in shades of, say, pink and green. The naturalistic colours could then be laid over the top of the tonal underpainting. This, he had learned – from his own father, from Degas, and others – had been the method of the old masters, and it was a method that he was thrilled to experiment with during the latter part of his career, in the late 1920s and 1930s.

He made striking images of – among other subjects – the Plaza Tiller Girls, Amelia Earhart's arrival in England, Lord Beaverbrook and Edward VIII.

While others might be disparaging about the use of photography, Sickert – at this stage of his career – was unapologetic. It helped, perhaps, that he knew that Degas had used photographic sources for some of his pictures, though this was never his stated defence of the practice.

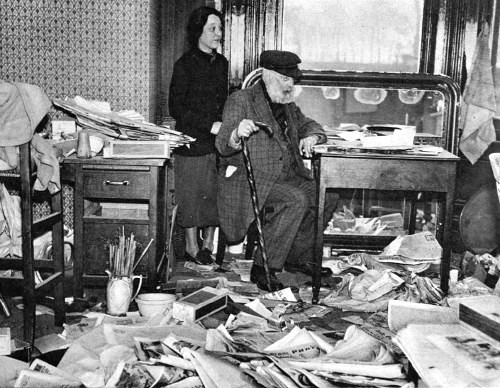

In early 1938 a photograph appeared – in both the Daily Telegraph and The Sketch – showing the 78-year-old Sickert and his much-younger third wife, Thérèse Lessore, in the artist's studio at St Peter's Thanet, surrounded by a sea of newspaper cuttings. It was very probably this striking image that inspired Roberts's fanciful picture of the elderly Sickert sitting up in bed, painting, while his wife cuts photographs out of the newspapers that surround the bed.

Sickert and Thérèse Lessore in his studio

The title of the painting, He Knew Degas, seems to carrry a hint of reproach: here is a great artist, joined by a golden thread to the giants of Impressionism, who has abandoned his high calling to copy images snipped out of the Daily Mirror. But of course it also carries an allusion – perhaps unintentional – to the fact that Degas himself used photographic sources for some of his works – and like all great artists realised that anything was permissible in the quest to create great art.

Home page | Chronology | Bibliography | Collections | Exhibitions

News | Gallery | Auction results | The artist’s house | Contact

List of works illustrated on the site

Catalogue raisonné:

chronological | alphabetical